In the Winter of my seventeenth year, I penned the following entry. Twas’ for me the titanic collision between my vigorous struggles to maintain (what I realized much later to be) Jansenist Christianity, and the undeniable deluge of my first love—

“February 19

Why am I upset by the fact that my love for her is not realized when any realization is the greatest folly I can acquire? If this is true, then all love is folly, and I return to a sad, enlightened condition [as in Ecclesiastes]. Or perhaps there is joy in this resignation.

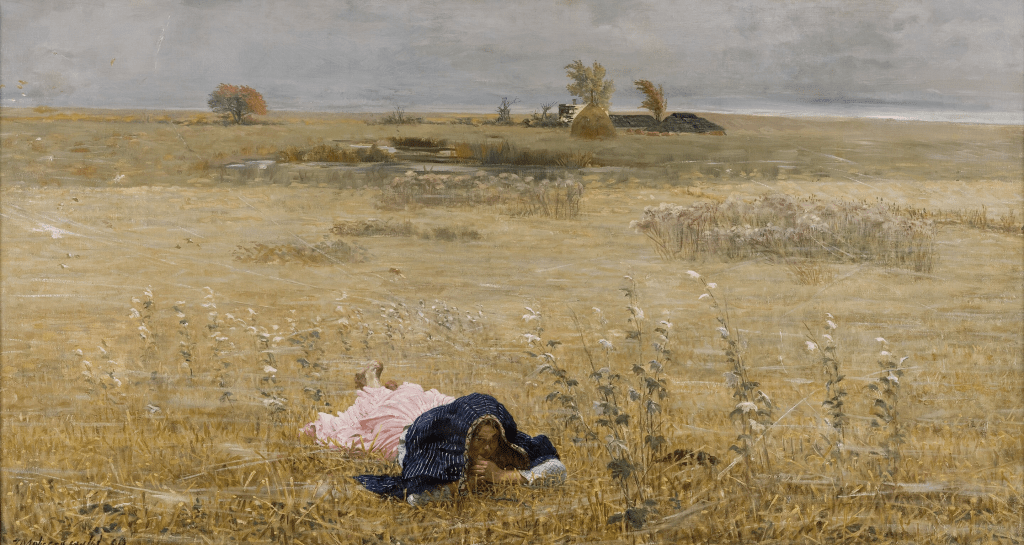

I stared at the clouds as I laid in my backyard, next to [my recently perished bonsai] Layla’s grave for a long time the other night. How much shame do I own when all I could think of, (and even now), is her, imagining conversations of what the clouds look like?

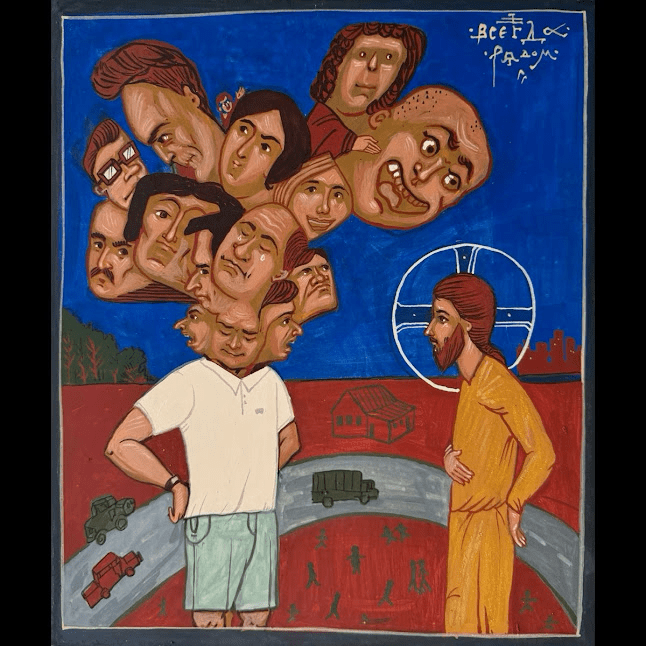

Despite the contingent basis of all pain, I keep returning to— despite my longing for that which cannot satisfy me and my folly— my continual realization of this: I always return to Christ on the cross, between two mountains in the valley.

‘Gazing up into the darkness I saw myself as a creature driven and derided by vanity, and my eyes burned with anguish and anger.’ [quotation from James Joyce’s Araby]”

There you have it. Vacillating between my harsh commitment to follow in the footsteps of Pascal & Kierkegaard, and the bliss of daydreaming on my love, I finally resolved that there was only one act left to be done. The invocation began for the minnesanger within to seize its serenading weapons of war; in a supremely strategic moment, in a fantastical frenzy of ecstasy— arming myself with a letter replete with voluptuous verses from The Sorrows of Young Werther— I let loose as a songbird, (dis)harmonies of joy & woe, rapture & guilt,

I have so much in me, and the feeling for [you] absorbs it all; I have so much, and without [you] it all comes to nothing.

Suffice it to say, neither my own confession nor support from Werther’s words did win her over. What is even more woeful— failing to heed the abundant proverbs which forbid courting your co-workers, I had to work alongside this girl quite often following this scene, only prolonging this false hope, the process of piecing together what exactly had just happened.

And I found that what precisely befell me was something that had been happening to me all my life, that really, happens to all of us all the time: the disharmony between the heart and the head. “Even if my Jansenism was wrong”, I scrutinized, “how could I be so logically convicted toward celibacy, but so weak to maintain?” I was as the king in Shakespeare’s Love’s Labour’s Lost, swearing off all love by the summit of earnestness— only to be usurped & completely capitulate to love by the very next scene! Thinking I was the first to experience this monstrous absurdity, how cathartic it was to find Paul’s words!

For that which I am doing, I do not understand. For I do not that good which I will; but the evil which I hate, that I do. (Romans 7:15)

This predicament— Akrasia, or the weakness of the will— is the existential terror I have felt to be most ubiquitous. By no means is it new to our scene. Akrasia is a force whose character Plato & Aristotle could only barely grapple with, and whose dizziness haunted Hamlet and the king of Navarre in equal measure. I shan’t need to give droll here about the woes it brings in e.g. procrastination; in this epoch of the Gutenberg Galaxy it is more intimate to us than the Greeks or Shakespeare ever could’ve conceived it being.

I must admit, though I eventually “got over” my first love, I don’t think I really even began to understand what happened to me until more recently; there is an illusive sense in which the problems we face can simply disappear, and we think them resolved. Deceptive as this may be, these problems may only disappear to reappear, awaiting only for the same catalyst in new clothes.1

Walking along life’s path, preferring not to balk before every paper tiger, (or even real tigers), it only seems natural to then get a grip on what more exactly is internally befalling us— divining both the deepest abyss & the loftiest sky.

When Paul writes For that which I am doing, I do not understand, let us stand unanimously. It begs a broad, even if vague question— how do we as individuals do what we do?

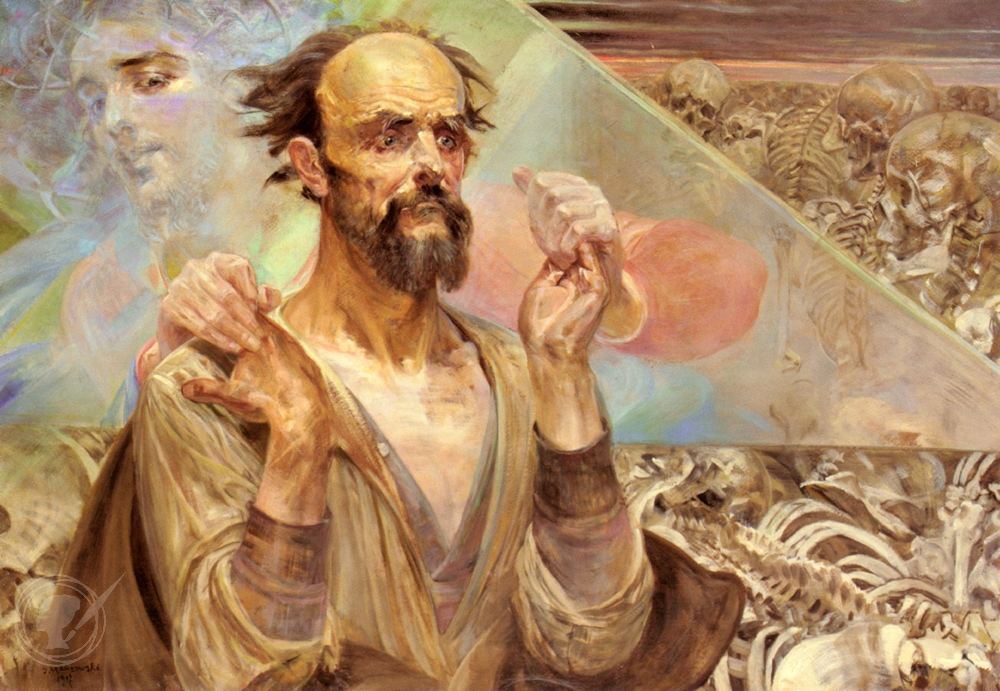

In an earlier meditation I reflected on the immense instruction to be had in the genre of tragedy; how any of our lives are, at any moment, susceptible to the worst tragedies conceivable, and finally, how Christ’s life may be presented as realizing this tragedy to the limit. Along a similar order of approach, turning to those who have most struggled with akrasia may illuminate our own struggles. Chart the course then to recollect the story of those traumatized souls, the psychological-martyrs, whose akrasia abounded to such a degree that they were the subject to pre-modern psychiatry— that is, exorcism. Here we see McGrath’s account of the post-Reformation exorcist, Johann Gassner,

“In response to those who doubted that he was really casting out demons, [Fr.]Gassner marshalled hundreds of eyewitness reports that seemed to prove the efficacy of his exorcisms. His dramatic battles with fallen angels invading the personalities of innocent people became a public sensation, so much so that an official commission was struck to investigate the matter.”

And further along, into the usurpation of exorcism by the origin of modern psychiatry through Franz Mesmer (the man who perfected the technique of hypnosis, from whence we have the word ‘mesmerise’),

“Mesmer’s defeat of the exorcist Gassner in 1776 decommissioned the Catholic priest and all that he stood for, post-Reformation demonology and witchcraft, not by refuting Gassner’s exorcisms (with hundreds of reported cures) or even debunking his methods, but by repeating his cures and explaining them in modern scientific terms.”

What is striking in looking into the work of either, is that they didn’t so much disagree on what was happening in their “patients” as much as simply muster different vocabularies to explain these happenings. Hence in the same paper does McGrath heap various “striking parallel[s] between exorcism and psychoanalysis”, which I shall provide in the footnotes2.

What we are really after is the conclusion drawn from these two schools, one ancient, the other modern, in treating those worst wrought by akrasia,

“What both exorcism and mesmerism testified to is the existence of a plurality of centres of intellection and volition in the personality. For the possessed these other selves were literally occupying forces, the malevolent minds and wills of the fallen, scheming to drag more souls into hell. Romantic psychiatry thematized the plurality as the duality of consciousness and unconsciousness. But this familiar binary does not accurately name the richness of the psyche unearthed by mesmerism, and its successor, animal magnetism. ‘The first magnetizers were immensely struck by the fact that, when they induced magnetic sleep in a person, a new life manifested itself of which the subject was unaware, and that a new and often more brilliant personality emerged with a continuous life of its own.’”

Nota bene: by the existence of a plurality of centres of intellection and volition, it is not meant, e.g. the three parts of the soul in Plato or Freud— rather, what is meant is multiple centres themselves. F.W.J. Schelling, in moving beyond the identity-philosophy he taught Hegel, wasn’t only the first to discover the concept of The Unconscious— he further realized there to be many centres which consciousness consists in, even if most of them are dormant or latent (and hence constitutive of many unconsciousness-es within us).

Reading this for the first time was rather jarring for me. Naturally, being most sensitive to ideas closest to our own identities, few things are as touchy as pontificating to someone the structure of their own selfhood. Believing in multiple selves sounded a bit (to put it in a mild way) bohemian. Am I not a whole, integrated, person? I’m sure McGrath could scarcely suppress his assassin’s smile as he followed up these natural thoughts with the story of Estelle,

“The story of little Estelle was made legendary by Freud’s French rival, Pierre Janet. In July 1836, Estelle, an eleven year old Swiss girl, was brought to one Dr. Despine, a physician with some knowledge of magnetism. She was paralysed and had suffered chronic pain her whole life. ‘No one except her mother and aunt could touch her without causing her to scream. She was absorbed in daydreams, fantastic visions and hallucinations, and forgot from one moment to the next all that was happening around her.’ (DU, 129) Despine magnetized her. Under hypnosis a second personality appeared, named Angeline, who prescribed Estelle’s treatment and diet, legislating that Estelle should be allowed to have anything she desired. ‘Let her act according to her whims,’ Angeline told Devine, ‘she will lead a double life: personality one remained immobile and in acute pain, desperately attached to her mother, respectful and deferential to her doctor, whom she addressed with the formal vous. Personality two suffered no paralysis, was intolerant of her mother and cheeky to her doctor, addressing him with the informal tu. Where personality one scarcely ate, personality two ate voraciously and indiscriminately. The romantic psychiatrists who studied the case took note that it was the primary personality that was sick; the latent personality was the healthy one.”3

Reading this, it flashed in my memory at once how as a youngster with divorced parents, two diverging personalities acculturated around whichever household I found myself in. The split in my parent’s marriage served almost as a split in my own, perhaps originally monolithic, budding consciousness. Really though, even if my parents didn’t divorce, the same would be true even beyond this— part of the greatest curiosities I had in middle school was witnessing how different classmates in different school periods brought out quite different parts of me. Some of these “selves”, I more identified with, & others felt more akin to My name is Legion, for we are many.

In the pop-psychology which has trickled down to our culture, it is quite natural to think of a healthy or whole self in terms of its homogeneity (being monolithic), and inversely, as an unhealthy self as haunted by plurality or heterogeneity (as in e.g. schizophrenia, etc.) Despite the contemporary diffusion of these views, I take it that the work of Sean McGrath, a man profoundly educated in German Idealism, Psychoanalysis, and Theology, has performed the essential task of rehabilitating Schelling’s Christian psychological research as to bear against one of its offshoots, namely, the culturally prominent monolithic model of the self popularized by Freud.4

I see Mcgrath voicing two essential lessons emerging from Schelling’s dissociative model of the self—

- “Whereas the monolithic self is biographically determined, never fully extricating itself from its personal history— the dissociative self is free. Its freedom does not consist in an absence of determination from the past so much as in its inexhaustible capacity to distantiate itself from whatever it once was. If Heidegger, a chief philosophical source for twentieth-century theories of the monolithic self, can write Dasein ‘is its past,’ the dissociationist says, Dasein is what it will be and what it wills to be.”

As someone who spent many a day studying Alice Miller, (her presenting one path which the monolithic Freudian psychology takes which intensifies its focus on how we are all determined by our childhood traumas), these sentences could not be more freeing.

- “Whereas for the monolithic self, the past is unsurpassable, being haunted by hidden memories and desires forcing themselves on the present, the dissociative self is united only by its future-orientation. What it anticipates in the future are possibilities, which are not limited by past actualities. Centers of consciousness, nexuses of memories, desires and thoughts, become dissociated from each other when the personality develops in some new direction. Only in a situation of plurality, differentiation, or dis-identification, that freedom is actual.”5

And hence, Schelling’s dissociative model of the self isn’t some kind of kingdom divided against itself, but rather, a plurality united by its future-orientation, or striving.

Are these kinds of freedom really something more than a chimera? It was astonishing at first to read, that with these two psychological discoveries in mind, the words of Paul may be taken seriously here—

It is for freedom that Christ has set us free. Stand firm, then, and do not let yourselves be burdened again by a yoke of slavery. (Galatians 5:1)

If Schelling’s discoveries are really a more accurate model of the self, the horizons opened to us might as well be a new America of self-understanding. We need not endlessly examine our childhoods, binge self-help books or motivational speeches, or even conversely, escape from life when none of these strategies work— to the utmost contrary6! These words of Paul, previously to us moderns so pollyannaish, are rediscovered in their fresh triumphant vigor!

By no means do horizons fade out here; we have only just begun. Having familiarized ourselves with the vast complexity of the self, let us depart for Schelling’s pragmatic realization about our question how do we do what we do?

The question of free-will is a question that some people care nothing about (common to many philosophical questions), yet others stake their entire lives upon. Though I must confess to, after reading Boethius, historically belong to the former camp, Schelling has subtly drawn me back into the question in precisely a way that connects it with what I do care about— how we moderns, with Paul and Hamlet, grapple with akrasia.

Schelling’s approach sweeps a vast territory. In his 1809 symphony-essay, On the Essence of Human Freedom, Schelling risks tackling a Theodicy with a much gnarlier concept of Evil than found in the theodical tradition of Leibniz, Kant, & Hegel. Through this, he ends up pinpointing the problem to lay in precisely how we conceive of human freedom. Delving even into the basic maneuvers Schelling makes regarding external determinism, the predeterminism of Kant, contingency, etc. would force us to get into the vast odyssey of this deceptively small book, thus, shamefully, I will only name a few of his conclusions for our purposes here—

Only in personality is there life, and all personality rests on a dark ground [Unconscious]… (pg. 75)

For the individual who wants to do anything, ironically, they will never be strong enough. Willpower, although it can be strengthened, shall reach failure just as a muscle does after so many reps. Our original intentions in doing anything become, not so much explicitly refuted, so much as suddenly obscured or distracted in precisely the critical moment we needed them most; the caprice and the fickleness of man is endless, with each and every different centre of the self endlessly taking charge. Here, no logical convictions can prevent them from slipping into the horror of that abyss. For most of us, especially countenanced by extreme circumstances, circumstances which do not allow deliberation, we are at the mercy of our given geworfenheit. For others of us, when we do have circumstances to think, we are reduced to a neurotic heaping mess— we are Hamlet, spending days anxiously working out what to do, ending up only to endlessly further doubt what we settled on—

Thus conscience doth make cowards of us all,

And thus the native hue of resolution

Is sicklied o’er with the pale cast of thought,

And enterprises of great pith and moment

With this regard their currents turn awry

And lose the name of action.

Doubt, not to be mistaken with discernment, is the endless tantalization of infinite possibilities. When our own will and intention turn awry, we need nothing short of a total surrender— not only of our Conscious, which can deceive itself through cognitively holding all sorts of propositions as true, and yet still be entirely vulnerable to akrasia— yet the entire Unconscious as well. Daily immersion of our Unconsciousness(es) in the flowing river of stories and practices is the only path to steadfast and long-suffering freedom. This is what it means to be a wise builder, who builds their house on a rock.

If only Hamlet had the Small Compline in his arsenal… What is a psalm after all? It is the prayer when one has forgotten how to pray… A psalm to enter the mind precisely when the mind is too weak to think… Though our eyes be completely shut, grasping onto, trusting in Ariadne’s thread, that it may lead to still waters… Yet the difficulty simply rests in the psalm appearing when it is most needed. Beware fellow children of the Gutenberg Galaxy, beware the loud lament of the disconsolate chimera! For the enchainment of past and future are woven in the weakness of the changing body.

Such is the augur’s eye which Shakespeare possessed, to see that the comprehensive shift in conditions brought about with the early modern period7 would pluralize the masters beyond precedent— ending only in Hamlet syndrome. No man can even serve two masters let alone thirty; and remember, whatever you wax anxious over, whatever you concern yourself with the most is your master. Alas, for Hamlet Syndrome is the lot of us articulate quixotic who fail to create, to give authority outside of ourselves, to give authority to the psalm!

This is why Schelling writes that we— we especially who abound in great education8 of many subjects and thereby are haunted by more caprice— do not have free will, but rather, it is free will which has us, or in his words—

We too assert a predestination but in a completely different sense. [We assert a predestination-by-Self] (pg. 53)

For reason of the insight that 95% of our daily activity & actions are Unconscious or automatic, it is only by immersing the deepest parts of our consciousness and unconsciousness in some kind of unitive future striving (paradigmatically, Religion), that we can then avoid akrasia through predestining ourselves9.

This strikes on precisely what a contemporary of Schelling’s, Novalis, wrote, that—

Temperament and Fate are two words for one and the same concept10.

Do not take my word for any of this. The most successful methodology in treating addiction to e.g. alcoholism in Alcoholics Anonymous, can trace its 12-step method, a method which begins with recognizing our own inability to control ourselves, and ends uniting the vast conflicting selves within me by a commitment to a “higher power”, through the psychological discoveries of Jung back to Schelling.

An infinity of thoughts come to us each day, yet they do not proceed from us— they come from what we predicate and surround our unconscious on and with. This is part of the point of Elder Thaddeus’s book Our Thoughts Determine Our Lives or Unseen Warfare— they are paradigms of pragmatic Christian wisdom regarding how we can pragmatically change our lives through incorporating the methodology of Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) centuries and centuries before CBT was ever formalized.

In essence then, we can either, willing ourselves to be an island, depend on our own willpower and intentions and be habitually haunted by the innate akrasia had from all of our selves warring anarchically, or we can simply give up to one higher, not with our lips and not only once a week, but unceasingly. Indeed, Paul’s insight in Romans 6 is that we can choose only slavery and addiction to sin, or slavery and addiction to Christ11, and nothing in between, lest we hear,

So then because thou art lukewarm, and neither cold nor hot, I will spew thee out of My mouth. (Revelations 3:16)

May we end this part then with Schelling’s final realization of religiosity as inextricable from willing itself— as the primordial overcoming and answer to akrasia—

“We understand religiosity in the original, practical meaning of the word. It is conscientiousness or that one act in accordance with what one knows and does not contradict the light of cognition in one’s conduct. An individual for whom this contradiction is impossible, not in a human, physical, or psychological, but rather in a divine way, is called religious, conscientious in the highest sense of the word. One is not conscientious who in a given instance must first hold the command of duty before himself in order to decide to do right out of respect for that command. [He goes on to give the example of Cato]

Already, according to the meaning of the word, religiosity does not permit any choice between opposites, any aequilibrium arbitrii (the plague of all morality), but rather only the highest resoluteness in favor of what is right without any choice. Conscientiousness just does not necessarily and always appear as enthusiasm or as an extraordinary elevation over oneself which, once the conceit of arbitrary morality has been struck down, another and much worse spirit of pride would happily have it become as well… [We must not be tempted to understand faith as the heroism of merely holding-to-be-true,] but in its original meaning as trusting, having confidence, in the divine that excludes all choice. If finally a ray of divine love lowers itself into an unshakable seriousness of disposition, which, however, is always presupposed, then a supreme clarity of moral life arises in grace and divine beauty.” (Pg. 57-58)

Why am I writing any of this anyway? I am writing because I have made, probably in no unique way, simple, yet foolish mistakes in my life which have led to slews of suffering for myself and others— ones which can affect me to this very hour. For me, it’s not that I didn’t already cognitively take myself to be Christian, and therefore, I had no excuse— rather, not thinking that my earlier decisions would lead to such suffering as they did, I wasn’t very discerning. Not learning from the imitatio Wertheri…

In a sense, I am glad to have entered into the suffering, for having thorns in my side is the most sobering kind of balm available. It’s not like you ever stop having thorns; they just change. Just as hunger is the best seasoning for enjoying a meal, suffering is, (to use the words from the parable), the best catalyst to turn us to looking at what we have built our house on. Will my house fall into a cataclysmic abyss, or shall I be on a rock which is lifted far above the world’s confusion? Have I truly counted the cost, performed not only the turbotax, but the long division of what it means to build anything at all, let alone a tower?

I have learned since that it was never bad to study all that I have studied, keep in my working memory all that I had in there— only, in comparison to the little room I afforded the words of life, the little mental bandwidth I gave to these precious words which could’ve saved me when I needed it most, I really did simply build on the sand. And one wishes to build on the sand not for no reason at all— perhaps on the sand we have a better view of the sea, or we are closer to the beach! Yet, whether we are accepting of this or not, remember what we are told, great shall be the fall.

Perhaps I am writing this so that I can further internalize the wealth contained in the words I merely organized, perhaps to have it in my heart as one clear thread, or perhaps to try and participate, however impoverishedly, in the what Northrop Frye calls, The human apocalypse, Man’s revelation to Man. With regard to all three of these reasons though, I know that there is still one more failure on my part— Kierkegaard puts it clearly in his Philosophical Fragments, that, The highest relation between man and man is the maieutical relation. If we are ever struggling to communicate something, most of all to ourselves, we see that it may only comprehensively be communicated through predestining and immersing our own Unconscious in that which is itself indirect, stories, the superstructure beyond ourselves like e.g. Christianity.

My communicative failure then, with all of this, is in not taking the maieutical approach, the best of which is literary. Some of the greatest philosophers therefore are hidden as authors (Shakespeare or, really De Vere, as one of the greatest, literarily discovering and popularizing the gist of the Unconscious around the same time that the mystic Jakob Böhme did, yet far more exoterically). May I atone for this soon.

The literary critic Northrop Frye, titled the second volume of his work connecting the Bible with Literature, Words with Power. A framing hermeneutical detail he takes is that, as far as the human psyche is concerned, there isn’t really any substantial difference between what we refer to as Mythology or Religion, and what we refer to as Literature. Excepting how one is more primordial, and another conscious, both still simply constitute the imaginative realm both immersing and guiding our Unconscious.

Since discovering Schelling and the immense influence of the Unconscious, since thereby delving more deeply into the tradition of the Words with power (a coleridgean phrase for literature), all that I have read seems only to redirect me more deeply to what I see as The Word (λογος) with all the Power. For despite all the philosophy and literature that I read, I keep coming back to the same river which infinitely exceeds my capacity to consciously think or grasp it; blissfully awash in the waters of life.

It’s not like Christ ever forces his cross on us. We are only told what the consequences of our actions will reap. Desire gives birth to sin which gives birth to death. It’s always so comical to me how, on a higher meta-level, no arguments are made as to why we shouldn’t choose death. It’s similar to Soloman writing the hypothetical: If you wish to see many good days, then meditate on the law of the Lord all the day long. There’s no time wasted arguing why you should want to see many days— the only fulfilling answer to this is seeing what many bad days look like.

Perhaps this is the immense consolation of a story (and what else is anything but simply a narrativization, stories!); it never chains you by syllogisms which initiate all these ad hoc rationalizations12, rather, it only gently points. And so gentle it is that it shall still let us tarry in our freedom, even if our freedom leads us down paths we really don’t want for ourselves or others. Despite the decades he spent honing his maieutical craft, even Kierkegaard eventually saw that sometimes all that can help us to have eyes to see & ears to hear is more suffering. And Schelling again considers suffering as a revelation–

“[The revelation is that] only in the opposition of sin is revealed the most inner bond of the dependence of all things and the being of God, as it were, before all existence (not yet mitigated by it) and, for that reason, terrifying.” (pg. 55)

Then God bless it. The true treasures of my heart are revealed as I suffer, and I see how much further I have to go. Perhaps this is why Soloviev realized the world not to end in some gradualist picture which slowly builds towards New Jerusalem (as I thought steeped in Hegel once), but it will all end as Christ said it would, with unprecedented suffering such that has not been seen since the foundation of the world. I am reminded also of what Seraphim Rose says, that “the psychological trials of dwellers in the last times will equal the physical trials of the martyrs. But in order to face these trials we must be living in a different world.” And may God bless it, for “We must through many tribulations enter the kingdom of God” (Acts 14:22). 13

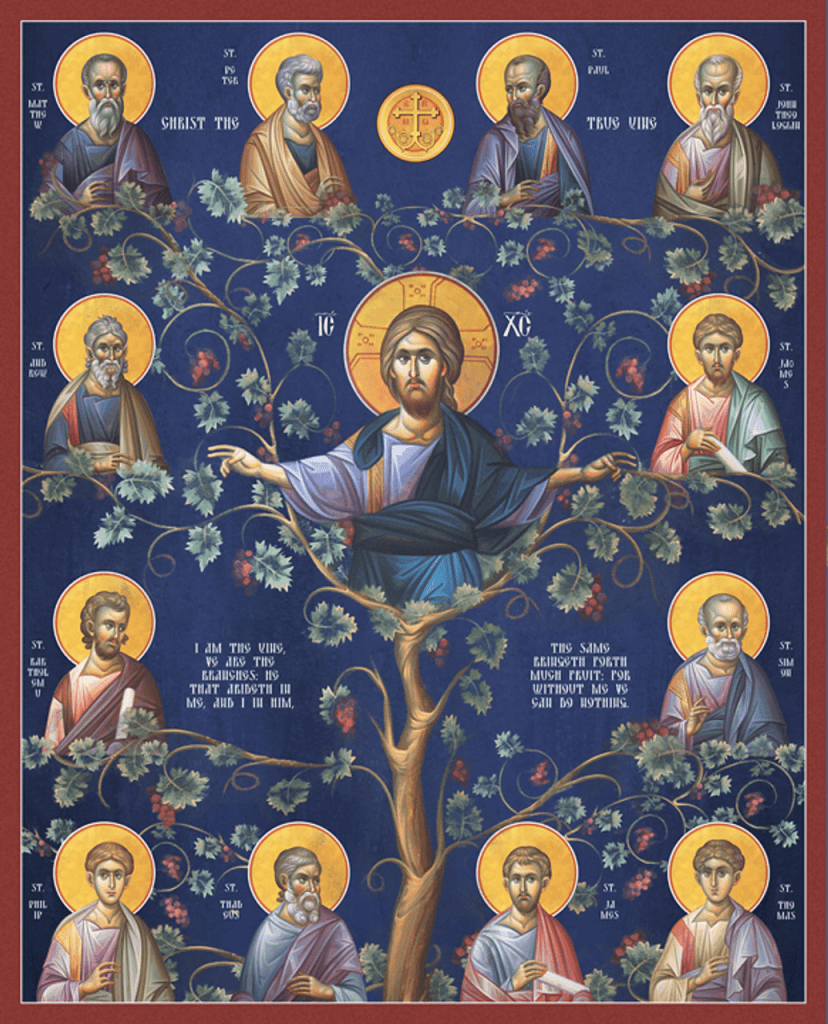

I am the true vine, Christ says, Every branch in me that beareth not fruit he taketh away: and every branch that beareth fruit, he purgeth it, that it may bring forth more fruit. Again, how comical is it that whether we fail to bear fruit, or we do bear fruit— we are told we will suffer either way. Is it that one suffering is an unhappy neurotic one, and the other a quiet joy found through suffering? A suffering which walks not by its own sight, but by a believing unbelief in Ariadne’s thread?

Is it true what you say? That every plant not planted by your Heavenly Father shall be uprooted?

I am the vine, ye are the branches, Christ says, He that abideth in me, and I in him, the same bringeth forth much fruit: for without me ye can do nothing. Yes, this makes sense, for where are there ever fruits without sufficient roots? Yet, even accepting this— who among us can dare to say “without me ye can do nothing”? How seriously are we to take Him at this? I suppose this is the question, one only to be decided between us and Him, alone in our closets. And I suppose that even the world itself could not fit all the books that would be needed to logically convince us of what to decide.

- As I have noted in a previous meditation, Kierkegaard describing this unconscious cycle, even in its happiest moments, as the worst form of despair.

↩︎ - “A second striking parallel between exorcism and psychoanalysis concerns the decisive role of language in effecting the cure. [For the exorcist], the power of the demon over the possessed depends largely on its hiddenness. Driven into the light of day, into the circle of a community of believers (often the exorcism happens with the family and friends of the possessed present) – into the light of language – the demon finds itself fatally disadvantaged. The possessed is no longer on her own with the possessor, and this enormously strengthens her psychological resistance.

Just so, the psychogenetic symptoms of [the modern psychiatry patient] Anna O disappear when she is given the opportunity to name their causes, re-experiencing them as she describes them in detail to [early neuropathologist] Josef Breuer. Breur’s approach to Anna O involved hypnotism, a technique that had been perfected in the nineteenth century by the magnetism and early investigators of the logic of mental illness (Charcot, Bleuler, Jung, etc.)

The therapeutic use of hypnotism shared several features with exorcism: (1) Setting up a situation for the exposition of the psychic disturbance – the trance, a safe place in which the defences of the ego can be ritualistically lowered so that the psychic disturbance can show itself, i.e., evade the censorship of consciousness, which is continually repressing it (thereby empowering it); (2) Establishing a personal connection of trust between healer and sufferer; (3) Neutering the unseen psychological forces by the use of language, both mnemonically and diagnostically. Like exorcism, hypnotism allows the patient to find a foothold in an interpersonal relation. Ending the isolation of the sufferer with the malevolent psychological oppressor frequently cured the illness.”

↩︎ - Again, though an extreme example, as it is with tragedy, these limit-stories only magnify a reality present in each of us.

↩︎ - Though, I cannot get into a full study of the dissociative model of the self against the culturally prominent monolithic model popularized by Freud (first of all, because it has been done by McGrath in better fashion than I could ever), I am drawing from three wellsprings of McGrath’s work in order to write this. For anyone who wants to see the Christian, Böhmean roots of Schelling’s psychological work, see: Schelling and the History of the Dissociative Self, or What would Schellengian Psychotherapy look like?

↩︎ - Minor rewording in this quote made. As an example of this second key, “When a man becomes a father, not merely physically but psychologically, when he gazes down upon his newborn child and understands for the first time, ‘I am a father,’ he dissociates from his pre-paternal identity. The man who was not a father does not disappear but remains an alternative centre of thought and action, which now for the most part lies latent, but which may under certain circumstances (in a dream, in intoxication, or in a simple change of environment) become active once again. The deactivation of an older model of the personality is not repression in the Freudian sense; it is the result of temporal transformation. The dissociative self thrives in self-opposition, much as a living being only grows by division and self-pluralization.”

↩︎ - I dare not say any of these pursuits are fruitless. To the contrary, many examples abound of some of these trees bearing fruit.

↩︎ - And the Enlightenment only proliferated this pluralization. Fellow Hamlets attend: we are never in control; we never were; and we never will be. Mapping chaos out inferentially or in thought gives only a diminishing security. And to think and strive as though it increased security will lead you straight into the halls of Elsinore.

↩︎ - Let us remember what St. Chrysostom said about the tribal islanders who took care of Paul and the rest of the shipwrecked in Acts 28, that these islanders have a far better conception of God than the worldly philosophers.

Take St. Anthony the Great’s word on this, if you will, “1. Men are often called intelligent wrongly. Intelligent men are not those who are erudite in the saying and books of the wise men of old, but those who have an intelligent soul can discern [διακρίνειν]` between good and evil.” – On the Character of Men and on the Virtuous Life, Philokalia, Volume 1

↩︎ - Is our coming to Christ itself a free act though? Schelling’s answer is quite complicated, but he gives it on page 53-54.

↩︎ - See this theme not only in Schelling, Novalis, Heraclitus (The road up and the road down is one and the same), T.S. Eliot (In my beginning is my end), but also in Christ Himself (Revelation 22:13).

↩︎ - As far as I understand it, this is also the main point made in DFW’s Infinite Jest, where, among many other overarching plots, a senior tennis athlete is juxtaposed with an alcoholic (and turn out to be not so much dissimilar in their “slavery” to either striving).

↩︎ - No narrativization chains you unless it has the explicit goal of enchaining or convincing you. In literature then, these narrativizations are rightly scorned as being moralistic, and in philosophy, these narrativizations are justly condemned as sophistry (and much, much more is sophistic than you could ever imagine). We have reached such a concentration of artifice that an unprecedented level of discernment is required now, sight which only becomes rarer and harder to maintain.

Moses himself laid out two different narratives, then at the end simply said: “I call heaven and earth as witnesses today against you, that I have set before you life and death, blessing and cursing…” The choice is freely mine…

↩︎ - Soloviev realizes this in his last work, War, Progress, and the End of History, and a Short Story of the Antichrist. Seraphim Rose writes this in a letter found here.

↩︎