In the famous Grand Inquisitor scene from Dostoevsky’s opus, The Brothers Karamazov, we hear the inquisitor speaking of the “universal and everlasting craving of humanity– to find someone to worship”. And further, “Without a stable conception of the object of life, man would not consent to go on living, … would rather destroy himself than remain on earth, though he had bread in abundance.” Having given an underlying rigor to these ideas in the last article- that the idea of all of our judgments depend on some constellation of commitments, some governing principles that we analogously worship– let us follow our last line of thought and then hasten ourselves to the mature German Idealist’s conception of Religion.

We left off in the last piece commenting on a shared kind of inattentiveness among religious institutions, specifically regarding the vast intellectual developments since the time of the Enlightenment. I take this to be especially tragic in not using such developments as an opportunity to further justify just how true they may really be. To their credit though, this inattentiveness is probably because of the unfortunate precedent set by the early Modern confrontation of Faith and Reason, with Reason trying to convince Faith that it is an inferior iteration of itself.

From the perspective of Reason, it has quite good reason to think this. One of the greatest takeaways of Kant’s critique of the faculty of human reason was in realizing that utilizing pure reason, i.e. reason unaccompanied by an empirical content or criterion with which to judge itself against as right or wrong, leads to subtle fallacies in logic, fallacies he specifically titled as paralogisms (a term carried over from Aristotle’s παραλογισμóς; the Greek usually translated as ‘fallacy’).

In his view, these paralogisms or fallacies were what all the “proofs for the existence of God” were ridden with, and he puts this point quite simply: to prove logically that something has the ontological property of existence– is like a merchant trying to improve their financial state by adding zeros to their cash balance. Existence as a predicate, is not something you can just make the cognitive judgment that, independent of empirical evidence, something has. According to Kant, we can say that something is or is not with regards to something in our sensory perception, but cannot logically make claims about that which is imperceptible.

Kant’s greatest challenge to the pre-Enlightenment religious is captured in one of his aphorisms: “Thought without content is empty”. Thought must be reasoning about a content which is perceptible (which in Kant’s thought presents a definite criterion). Without a content of thought being available in the experience of perception, and just as Kant noticed about the rationalist school of philosophy antecedent to him— we are using reason about subjects to which no criterion is even available, and hence, our talk is empty! What a lousy beginning for philosophy!

Accordingly may we see why Kant began the labor to build philosophy on fertile “apodictic” ground anew. Kant makes explicit the thought that when we try to make claims without any empirical touchstone, pure reason is able to prove both that God exists, and that He does not— something he brilliantly demonstrates in the fourth antinomy. The very fact that we can both prove and disprove the existence of a necessary being through pure reason led Kant to argue that it was ridden with paralogisms, and further, without any available empirical criterion to use for proving or disproving the existence of God, we must resign ourselves to never knowing, i.e. agnosticism.

With this worthy challenge in mind, I wish to lead us towards what the young German Idealists thought about this.

Let us begin with the paradigmatic question, a question Kant thought unanswerable and that Nietzsche’s last man can find no sufficient answer for (hence their positions morphing into agnosticism and utilitarianism)– indeed, perhaps the most significant question that can be raised to anyone: there is a plurality of religions, each of which claim for themselves, the capital-T Truth— can we find a method to adjudicate the variety of claims one may find in Religion, cognitive and otherwise, such that we may understand a singular religion as True, as opposed to the others?

Perhaps we may hear a voice saying that it just takes “faith”, and that we cannot penetrate into the inner mystery of religion— sure, but faith in which particular religion’s content, and why? I invite you dear reader, if you believe e.g. in Christ, why do you believe in the Christian conception of God as opposed to the Islamic? The Jewish? The Hindu? Or even the secular conception of God as a contrived figure of the human imagination?

Perhaps owing to the aforementioned trauma between Faith and Reason’s first confrontation, such a question is unfortunately regarded by many religious rather stigmatically. It is this taboo, this kind of mass unconscious confirmation bias feeding a recalcitrance toward justifying why we believe what we believe, this quietism that I take to be the source of immense suffering. It is a quietism that drives the many lonesome souls who, only finding doubt in themselves as though it were some isolated occurrence, live unhappily either outside of the traditional organized religions or as Nietzsche’s heralded last man.

This question is such a significant one for anyone thinking about Religion because when there is a dissent in any scientific field, say, in the field of Physics, we can rest assured that the true theory of gravity may be discovered or proved through falsifying the false theory according to some certain criterion, e.g. of empirical observation– Indeed this was Kant’s main point, the natural sciences, because they make judgments about that which is empirical, are far more reliable than Religion or Theology, which have no clear criterion by which they are true or false.1 After all, the reliability of the natural sciences would go on to become a hallmark of their purported reason for triumphing over the traditions of religion: Copernicus’ theory of heliocentrism supplanted the Catholic Church’s sponsored geocentrism.2

Religions don’t exactly make easily verifiable empirical claims like Physics does, and even, arguably, when they do, they are often mistrusted in favor of the natural sciences. Instead, the sort of claims that Religion does make are actually philosophical. Religions make metaphysical claims about the absolute nature of reality, the independent ontological existence of supreme Being(s), claims even of who we intrinsically are as humans. Part of Kant’s project was in calling out the various early modern philosophers who tried to build monolithic metaphysical systems, (and by extension, religions which implicitly did the same) as engaging in a nonsensical practice, that pure reason alone could never be trusted to penetrate into attaining the truth of such matters.

It is here we find ourselves at Hegel’s genius methodology. Let us answer the question of a possible criterion for Religion explicitly after making our way through Hegel’s general approach. The beauty of his approach is that he gives no obviously biased and monolithic hermeneutic with which to straightaway vindicate what he already agrees with; no, in this way he differs from almost every philosopher of metaphysics before him who posited quite reductively that everything just came down to x.3

His is an approach which alone can give full credence to something like the diversity of viewpoints in philosophy, for he understands philosophy as a distinctively historical tradition concerned with answering differing, yet related questions, questions which exhibit a seemingly inexhaustible capacity for being evermore critical of our presuppositions. Similar to his conception of philosophy, we can only appreciate the diversity of Religion (especially its diversity of claims!) by fully appreciating it as a history.

Conceiving of these traditions as foremost historical traditions doesn’t mean they merely concern themselves with being a compendium of dates and names– Caesar was born in such and such year– rather, Hegel sought to articulate the possible inner coherence disclosed throughout the events of history, again, not through straight away stamping his ideology on the whole thing, but through simply letting the history speak for itself.

“No man is a hero to his valet”, was a proverb Hegel used to illustrate how so much philosophy and history was playing valet, so to speak- something he elaborates by adding to the proverb “This is not because the hero is not a hero, but because the valet is a valet.” It was, just as a valet thinks in seeing their master in his most weak and pathetic moments, e.g. needing help getting dressed, being fed, etc. that similarly, historians and philosophers are reductive regarding the grand wealth and substance of the world and of history by reducing it to one point of view.

In contrast to those particular methods, Hegel’s method is as Kojève claims, no method at all, or, if it may be called anything, it is a distinctively holistic method. It is trying to re-articulate every single way the world, or history has been conceived so far, retracing the philosophers and theologians of old, and putting these differing points of view into a grand dialogue with one-another. Being within the same tradition of dialogues as Plato, Hegel recapitulates the process of how they worked out their logical differences, their contradictions, a process we have already witnessed with his earlier explication of the dynamic between Faith and Reason, a process we bear witness to constantly.4

“He who looks at the world rationally, the world looks rationally back” – G.W.F. Hegel

“He who looks at the world reductively, the world looks reductively back” – Robert Brandom

With Hegel’s methodology in mind, let us assemble the last raw materials for understanding his conception of the criterion for Religion. The history of Religion is a process which, much like anything else in its infancy, was not in its earliest moments yet conscious of what it was a process of– it was only through its own initial unconscious development that it gradually comes closer and closer to consciously understanding and expediting the process of what it was implicitly being guided toward, working toward all along.

It is similar to the development of the concept of a truth-criterion in the history of philosophy, the thing against which we understand ourselves as wrong or right. The explicit concept and understanding of a truth-criterion developed through constantly implicitly or unconsciously breaking it5 (something that Hume made clear, and then Kant further appreciated in hitherto unparalleled rigor)!6

As a meta-historical question, to claim any definite “goals” of distinctive historical traditions with such a stature as Philosophy or Religion are certainly claims not without deep controversy– despite this, we must admit common themes in either emerge, themes of figuring out what is going on and why, themes of figuring out how we should live, and why. It is in following these more uncontroversial themes that our raw materials shall gain form.

Religion, being far more ancient as a tradition than philosophy, took far more of a mythological shape, providing answers borne out of thousands of years in the crucible of developing human consciousness. With the sheer quantity of ancient accounts claiming to have seen great beasts, giants, anthropomorphic gods & heroes– such inconceivable sights may be laughable to us moderns, and even more laughable as proposed answers for why lightning occurs— yet those who laugh in place of feeling a deep reverence take far too much for granted.

Take a straight wooden stick in your hands. Put part of that stick in the water before you. How does that stick look? A bit bent, eh? Yet, taking it out of the water, it appears completely straight again. Can you imagine what this was like for ancient peoples, they without the concept of refraction, to make this phenomena intelligible? Can you imagine everything else they must’ve seen and heard– just as very young children still do today, unfamiliar with the ways of the world & possessing descriptive capacities armed with the most fantastical of imagery— and truly believing that it was as they described it was?7

Taking the conception of Religion as the search for a coherent worldview further, organized religions, and what is understood today as “spirituality”, are groupings to capture the ‘meaning-making’ that we as humans inevitably employ toward reality and ourselves. They are incipient as a pattern-recognition that eventually, thinking itself to have come upon essential patterns, acculturates around such essentialities into fully-fledged & deep rooted cultures. In each interfacing with reality we’ve, since the dawn of time (dawn of consciousness), increasingly made sense of what was going on in and around us. In the broadest and most uncontroversial sense, this is what Religion is, and what its unfolding history is a history of.

Religion then, contrary to Kant, does have a criterion by which it is wrong or right– and an empirical one at that– one that is perceptible in its history, and revealed by the process of its unfolding. This criterion is implicit whenever one particular religion– take what Anthropologists consider the earliest religions or spiritualities: Animism, Fetishism, and Totemism– is succeeded by others: Paganism.

Why does this succession occur at all? We may take as an example, the history of Religion’s transitions from Animism, to a more complex Paganism of incredible variety, and emerging out of Paganism, the first most radical religion of the ancient world– Judaism. Judaism is radical precisely because it is the first religion to conceive of divinity as, not various sets of animal and fauna (Animism), hybrid half-animal half-humans (Egyptian polytheism), or even a chief limited number of purely anthropomorphic gods (Greek polytheism), no, it conceives of God as the most abstract concept of all– nothing that can be identified on this Earth, absolutely no-thing.

What is occurring historically, and again, quite uncontroversially, is a distinctive sense in which certain religions are developing out of, and taking the torch of, previous ones. As said earlier, this cycle of succession isn’t a merely arbitrary history– in fact, when we look closer at the succession process throughout the history of religion, we may actually see the underlying reasons for why such a succession took place– sure, on the surface, perhaps mythological reasons– yet mythologies which are actually revelatory of a robust logical framework; one robust logical framework evolving out of the newfound incoherencies of another.8

The very bare empirical reality that there is this living & breathing process of succession or evolution that history is sopping wet with, an evolution which doesn’t merely temporally succeed but also, even if unconscious of itself as logic, logically reforms itself according to what it sees as incoherent or contradictory in the logical framework it is succeeding from– this reality discloses the criterion by which we may understand a particular religion as best fulfilling the broadest goal of Religion in general– the search for a coherent worldview.

Such a search is manifold, even if unconscious to them. One of the most common facets of such a process of investigation is making error as a phenomenon intelligible. It is realizing how the stick is really straight, even though it erroneously appears to be bent when we put it in the water. Beyond cognitive judgments, we are, after all, constantly making mistakes, or at the very least, not being as efficacious in any posited intention or goal as we can, and the capacity of identify this– the capacity of gradually revealing errors founds the cornerstones to what will become fully-fledged traditions, traditions which may see the blossoming of their own distinctive and essential ways of ‘going about things’, i.e. normativity, one pragmatically used to derobe commonly encountered errors.

Error happens, indeed, states of affairs arise that we feel to be horribly painful or uncomfortable, and so we think to ourselves– well, I want to avoid whatever that was! We find others who empathize– well, let’s avoid whatever that was! Essential ways of ‘going about things’ acculturate into institutions, institutions which attempt to maintain their essence and spread themselves (what they consider ‘The Good’) through time and space. This is certainly a noble striving, yet one of the hardest to achieve efficaciously, there being a structural irony in any such tradition attempting to maintain an essence which cannot remain what it is essentially while also coherently articulating itself to an emerging epoch.9

Quite unsocratically, confronted by this contradiction, institutions often develop a dogmatism that becomes the source of much suffering from organized religion, which forces everyone to commit violence to their consciousness by making them choose to identify between two equally essential parts of themselves (which the organized religion, out of their fear, divides into opposing sides). It is a perennial theme, carefully adjudicating the balance between being and becoming. One of the reasons I appreciate Christianity is because I believe it is the only religion to fully recognize this structural irony, and even builds itself upon such an irony– something I write about in “Why I Love the Gospels”.

So we give errors like these structural ironies a name– in a religious vocabulary, the primitive conception of error emerges as sin– we try and map out its inferential character: how can I avoid that? What conditions make it possible? How can I minimize such conditions? If we find ourselves in it, how can we make it as easy as possible to protect ourselves from it? This is the sublime pragmatism– indeed, even empirically verifiable– that unfolds throughout the history of Religion, invaluable wisdom we usually just inherit culturally but rarely, if ever, drink from the source.

Beyond this, the moral conception of sin develops variantly into the logical concept of cognitive error. Although they weren’t aware of it as they were going through such a process, the development of Religion is an almost identical forerunner to the development of Philosophy. Hegel constantly advocates for the equivalence of content between the two (once they are both somewhat conscious of what they are after): they both are concerned with the Absolute Truth, they both demand their adherents to set aside personal desires or personal presuppositions respectively in order to properly interface with the Absolute Truth, both even are in this way worship.

Hegel admits a single difference between them: Religion takes the method of expression according to Vorstellung, a mode of expression translated as picture-thinking, or representational-thinking, a kind of preconscious rationality– rationality before it is conscious of itself of being rationality, much akin to art— and Philosophy expresses itself according to an increasingly rigorous and self-critical conceptual-thinking (rationality fully self-conscious of being rationality).

On the side of picture-thinking, Religion has for itself mythologically the same goal as art does in a more purely pictorial way– to express in the form of finite vehicles (personifications, or in the finite dimensions of color and form), what is infinitely expressible as the palette of the human psyche, the truths of the human condition, etc. Art and music, we may keep in mind, was principally religious until the Renaissance.

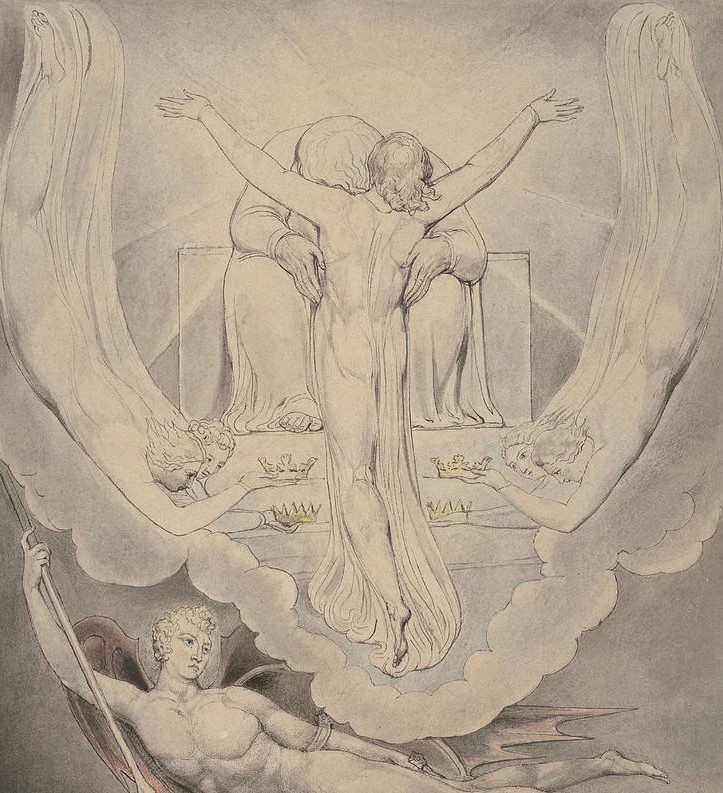

On the side of conceptual-thinking, this mighty power– the power of scrutiny or simply being critical– is a power that gradually develops in and through the history of religion. At first it is unconscious, a dormant faculty, stifled by being, often, normatively incumbent to unenlightened despotism. Yet when its wings become fully fledged, Reason, much to the credit of the early French revolutionaries, certainly deserves its astonishing character– it is the blossom which succeeds its stem, yet does not refute it; the ominous portents of which fate the end of the tradition it appears in, filling the dogmatic with a dread that so confutes them, they often cope through murder.10 It is the faculty by which Socrates devotes his being, the principle (Εν αρχή ην ο Λόγος) that Jesus Christ is an incarnation of– and therefore, it is only fitting that they both share the same gruesome fate.

Looking at the relationship between Religion and Philosophy, we may see how the latter is recapitulating the process and history of the former in an increasingly explicit and expedited manner, even comprehending Religion better than Religion comprehends itself, understanding just how true some particular religions, yes, even their cognitive claims, really are. This is not to say that one is superior over the other– in Hegel’s view, they really are just the same thing, or at least, two sides of the same thing that we tended to separate after their “break-up” during the early Enlightenment.

The beauty of Hegel as a philosopher is that he is one of the only philosophers to fully appreciate why this break-up happened, and indeed, how the break-up was inevitable with certain latent contradictions implicit in their pre-Enlightenment unity merely coming to the surface in the Enlightenment. It is a theme of Hegel’s that initially identifying the distinct identities of things leads us to irresponsibly oppose them to one-another, construe them as separate and having nothing to do with one-another, when in reality, upon closer scrutiny, they are rather distinctive moments expressive of the same underlying unity.

In understanding any respective mythology (which is both created and discovered by any particular religion) to be expressive of and succeed one-another as progressively coherent robust logical frameworks, we may provide an answer to our original question: the religion that is expressive of the most logically coherent framework, i.e. that has no identifiable logical contradictions is the religion that is capital-T true.

Quite the standard to live up to. Having assembled these raw materials, we are now finally ready for Hegel’s mature conception of Religion. When we say that Religion is the unfolding search for a coherent world-view, we may flesh this out further to say: Religion is the search of finding a coherent finite vehicle with which to fully express the infinitude of the Absolute Truth.

This is all to mean the pattern by which the history of Religion unfolds, both chronologically (with few exceptions) and certainly logically – is the pattern of increasingly coherent finite images, or mythologies which express more deeply an underlying infinitely expressible inferential character. Mythology after all, as its etymology goes, can then be rendered as the coherent interrelationships found within any mythos revealing coherent interrelationships found within its corresponding logos.

With regards to the very inception of philosophy, we may look to the pre-Socratic philosophy and Thales, the first conscious attempt to answer questions without depending purely on mythology (Logos instead of mythos). What Hegel realized much later was that just as Faith and Reason are two sides of the same thing, similarly– Mythos and Logos are two different expressions of the same underlying Absolute Truth– and further, that each is only complete working in tandem with the other.

This last claim is much more bold, and forms the justification for the more fleshed out definition of Religion as seen above. If it is true, I believe it is the single most significant idea for our reality here and now. It fully addresses Kant’s critical agnosticism and provides a brilliant explication of the unfolding of each particular religion; it is a skeleton key to face reality that is completely undiffused in the contemporary ways of thinking about and approaching life in general, let alone religion, and if diffused, I believe it has the power to totally transfigure the entire landscape of culture. In truth, I have already seen just how valuable of an idea it is, and so, like a painter struck by his image in a sacred moment, I will attempt to give the essential expression of this idea in the last essay of this series.

- Kant’s insight here I find to be especially revealing regarding the shortcomings of Pre-Kantian discussions regarding religion. How can anyone argue that one religion is “better” or “more true” than any another without first establishing a settled criterion by which any such value-judgments are intelligible? Hence I find most “debates” on religion with ‘pre-Kantian interlocutors’ to, unfortunately, be rather impoverished, them mostly consisting of dogmatic assertions of one’s own worldview, while trying to externally undermine the other’s; few if any at all getting to the most profound inner-ground of what Religion even is let alone how any particular religion immanently innovates out of another one…

As Hegel says again: “It is not difficult to see that the way of asserting a proposition, adducing reasons for it, and in the same way refuting its opposite by reasons, is not the form in which truth can appear.”

↩︎ - Kant, perhaps with some conceit, stated that his critical enterprise was a “Copernican revolution” for philosophy. Hegel would write later that the Copernican revolution that Kant began was incomplete, and was to be completed in German Idealism.

↩︎ - That everything comes down to x, is a theme in philosophy. In ancient Greek philosophy, the “x” in question was known as the arche (ἀρχή), or underlying principle of reality. Thales, the first philosopher, thought the arche to be water, Anaximander thought it was apeiron (the Unlimited), Anaxagoras thought it was nous. We may even go further to say that Böhme thought it was the Ungrund, that Descartes thought it was the Cogito, Spinoza thought it was pure undifferentiated being, and that Kant thought it was the Unity of Apperception… sorrowfully, the reductivity doesn’t really end until Hegel (and even then, it sadly continues after Hegel due to a plethora of contingent historical reasons).

↩︎ - All of this is the substance of his early work, The Phenomenology of Spirit, and if he had written nothing else, it would be this method alone that I think is most valuable from him.

↩︎ - There is a paradox nested in this dynamic that is raised in Plato’s Meno, ~’How can we learn something, ask a question about something if we don’t already know what we’re searching for?’. Such a paradox is brilliantly elucidated by Hegel in the Introduction chapter of The Phenomenology of Spirit.

↩︎ - Kant, in his Critique of Speculative Theology section of the first critique, will argue that Hume rightly limits human reason but fails to draw determinate bounds– hence Kant’s project of drawing up these bounds by critiquing the faculty of reason.

↩︎ - The Renaissance historian Giambattista Vico, the first historian to try and make a history of Man without dogmatic reference to the Bible, expresses this dynamic illustriously in The New Science. As another story goes, Goethe brought the writings of Vico back from Italy to a circle that included Herder & the younger Hegel…

↩︎ - To reveal the rational kernel underlying the succession of mythologies as robust logical frameworks is a subject matter now studied by the fields of Analytic Theology & Comparative Theology. If I appreciate Hegel for any other reason, it was for inaugurating this venerable task of teaching Religion to speak philosophically, especially in an Enlightenment post-Kantian dialect. Among his forerunners may be counted such men as the Cappadocian Fathers, most notably, St. Basil, who were the first to articulate the logical relations of theology in the language of the pagans Plato and Aristotle.

↩︎ - I use the term “essentially” here, in its highly technical original meaning as birthed by Aristotle- “τὸ τί ἦν εἶναι” – essence as opposed to accidents: something that makes something what it is, without which the thing would no longer be what it is. My main claim is that the essence of many traditions (and this is ironically implied by the very term: tradition), acculturates itself upon a particular content which, when confronted by a genuine scrutiny belonging to a later & newfound epoch, becomes dogmatic as to maintain itself. If it took this genuine scrutiny seriously, the tradition in question runs the risk of saying about itself, “We do not have the Absolute Truth”, a confession that is perhaps the hardest of all to admit to ourselves when we are steeped in a particular tradition that we are attached to. The grand irony present here is that at such a moment, the tradition no longer Socratically devotes itself to The Good, but rather to sentimental attachment. I appreciate Hegel so much because he builds his entire “tradition” upon making explicit this story of logical and existential succession, known popularly as dialectics.

↩︎ - This theme may be seen, albeit in a negative light, in Nietzsche’s The Birth of Tragedy.

↩︎

I am waiting patiently for the final installment.

LikeLike

I am very glad to hear. What do you think so far?

LikeLike