These three essays may be read standalone, yet read together follow an emerging line of thought regarding, what I believe to be, the most significant topics of human existence. In following the inquiry at hand, we see presented the illustrious interweaved story of the history of religion and philosophy, two stories, or better yet, vehicles which the reader may find as upwelling fountains flowing forth their own self-consciousness in fathomless depth and breadth.

Indeed, this is the greatest gift, that we do not have to reinvent English in order to speak it; conversely, this is the greatest tragedy of our age, that so much of what we do and think has already been rigorously made explicit in some of the greatest geniuses of world-history, laboriously mapped out in an ongoing tradition of dialogues— and neglecting to familiarize ourselves with such wealth, we may live our entire lives marching confidently along already well-trodden paths, alleys well studied by many of old who prophesy their leading only to death.

Yet what does this mean, a path that leads only to death? Let us begin our journey.

***

I remember once, as a boy no older than twelve, driving with my Father to the orthodontist’s. As a drizzle began from the overcast sky, my Father put to me a question that gave me great pause, a question of my thoughts on religion. At first I was surprised, this being quite a peculiar question to hear from him at the time– in our familial milieu religion was rarely, if ever, spoken about. Sure, it was something that was mentioned on TV, perhaps even from time to time acknowledged by someone– yet there was some unspoken understanding that it wasn’t real, or at least, never as real as the really real things.

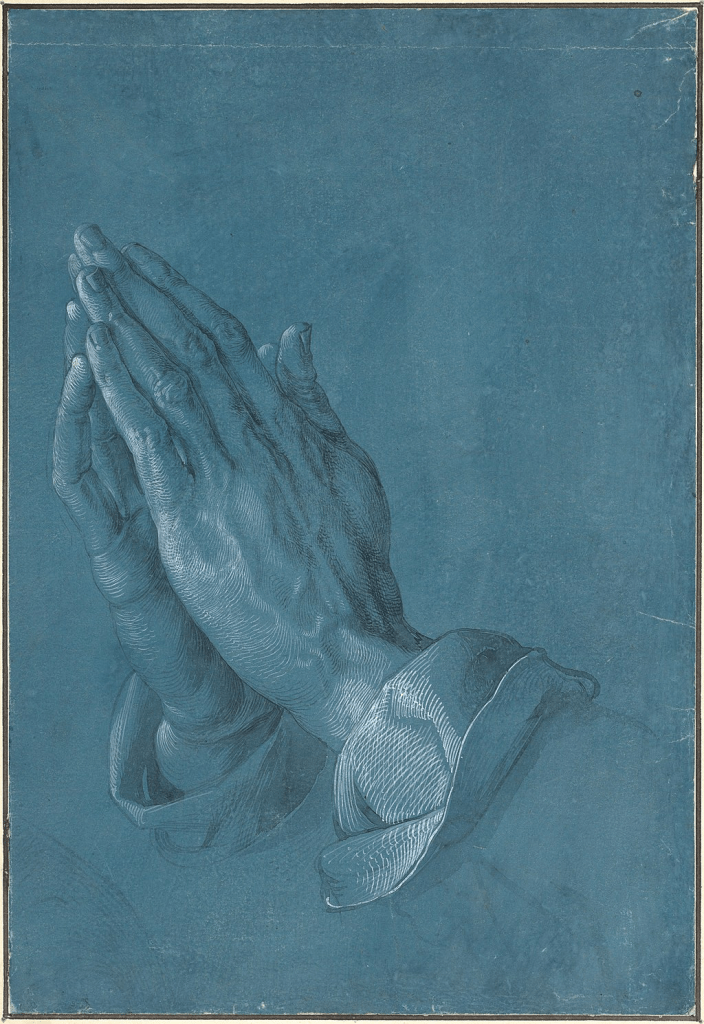

At the time, religion was quite the nebulous concept to me, which is how I eventually presented my thoughts, “Religion seems like … something people tell themselves in order to feel better …”. Collecting my thoughts on a vivid gray cloud, the young American pragmatist in me made a specific point on what I heard of as prayer, “Instead of praying about something, it seems better to just take steps to actually solve something”. After a few minutes of us finding mutual agreement in one-another, the topic switched and wouldn’t come up for several years later.

To this day religion still can stand as this vaguely peculiar construal of reality, especially from the perspective of my boyhood. Over those coming months, it became an increasingly fascinating, even if specious, phenomenon to encounter– encounters with the reality outside my home that were unintelligible to me; my home for me, as it is with any child, being a first “truth-criterion”.

Sometimes these encounters were as subtle as a friend at school who, when speaking of “God”, suddenly became serious in their demeanor. At other times it was more explicit, with another schoolmate leading us to a concealed zone behind the playground, revealing to us bits of cracker and grape-juice packets he smuggled into our afterschool program, saying, “I brought this for you guys! It’s the body and blood of Jesus– let’s eat it together!”

For me, the reverence of such a situation was so foreign, something only comparable to the 30 second silence we took during the pledge of allegiance, yet it was simultaneously enticing, as if it were a deepened experience of the pledge. “Thanks dude!” I exclaimed, taking what he mysteriously referred to as communion.

Since those days, a combination of growing up in the diverse culture of Tampa– where nearly all of my boyhood chums were either Christian, Hindu, Muslim or, failing to place their confidence in the claims made by each respective tradition, becoming secularites akin to myself– that and a burgeoning interest in philosophy guided my interest in this mysterious phenomena entitled religion. As I began to venture into nature more, I started to ask myself in wonder: what is this? This shall be our starting point.

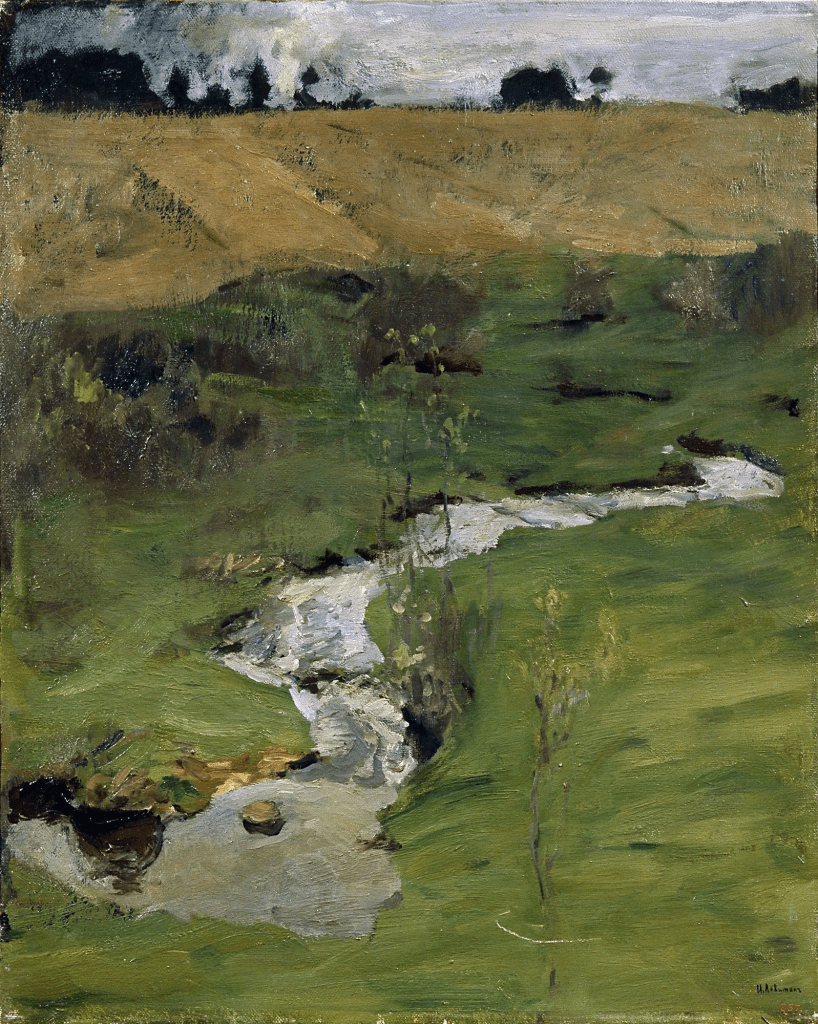

“Last evening I climbed a cliff and looked down at the sea from the top – I started to sob, and sobbed violently; that was eternal beauty, that was where a human being felt his own utter insignificance.” – Isaac Levitan

“Art does not simply reveal God: it is one of the ways in which God realizes, and thus actualizes, Himself.” – G.W.F. Hegel

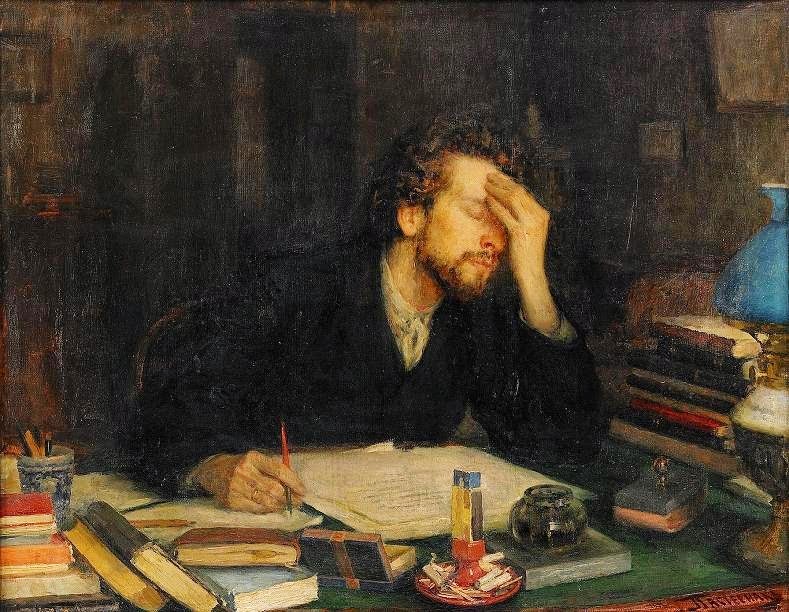

Although I grew up outside of any particular organized religious tradition, entering into my early teenage years began an intimacy with a more numinous dimension of reality. I was not religious, and never would’ve considered myself as such, yet there were moments where reality found itself through my eyes ‘coming together’, a moment where all of nature stood looming over me in this kind of deafening coherence, an emanation demanding ineffable reverence. The artist aptly called the “Poet of Nature”, Isaac Levitan, captures this well in his two paintings above.

It was specifically encounters with nature as I rode my bike in freedom– the lofty and infinite blue of the sky, a blue that I could almost touch, along with the myriad majesty of clouds. This was a sentiment I found to be expressed by Tolstoy in a scene from War and Peace, a scene where one of the protagonists, Andrei, is bludgeoned in the head during a battle of the Napoleonic Wars–

“‘What’s this? Am I falling? My legs are giving way,’ thought [Andrei], and fell on his back. He opened his eyes, hoping to see how the struggle of the Frenchmen with the gunners ended, whether the red-haired gunner had been killed or not and whether the cannon had been captured or saved. But he saw nothing. Above him there was now nothing but the sky- the lofty sky, not clear yet still immeasurably lofty, with gray clouds gliding slowly across it. ‘How quiet, peaceful, and solemn; not at all as I ran,’ thought Prince Andrei- ‘not as we ran, shouting and fighting, not at all as the gunner and the Frenchman with frightened and angry faces struggled for the mop: how differently do those clouds glide across that lofty infinite sky! How was it I did not see that lofty sky before? And how happy I am to have found it at last! Yes! All is vanity, all falsehood, except that infinite sky. There is nothing, nothing, but that. But even it does not exist, there is nothing but quiet and peace…’”

With these experiences in mind I must ask the pivotal question: were such encounters with reality my own subjective personal contribution? A kind of projection that I added to what was already there? Or, were such moments inevitable, themselves structured according to a kind of psychologically innate archetypal organization of reality– one without which reality couldn’t be processed? I shall be concerned with navigating these questions, questions of many subsidiary forms that constitute the most significant inquiries into religion.

Before tackling such questions head on, allow me to finish my story– in those first boyhood encounters with nature, something more started occurring for me.

As my escapades became longer, as they grew more arduous through the Floridian Summer, my numinous moments simultaneously heightened. In preparing for a half-marathon of cycling, in the same way I would intuitively drink water, I also found myself listening to songs about Napoleon, songs lauding the grandeur of his exploits, his heroic character– all this as a way of drawing strength for my own endurance.

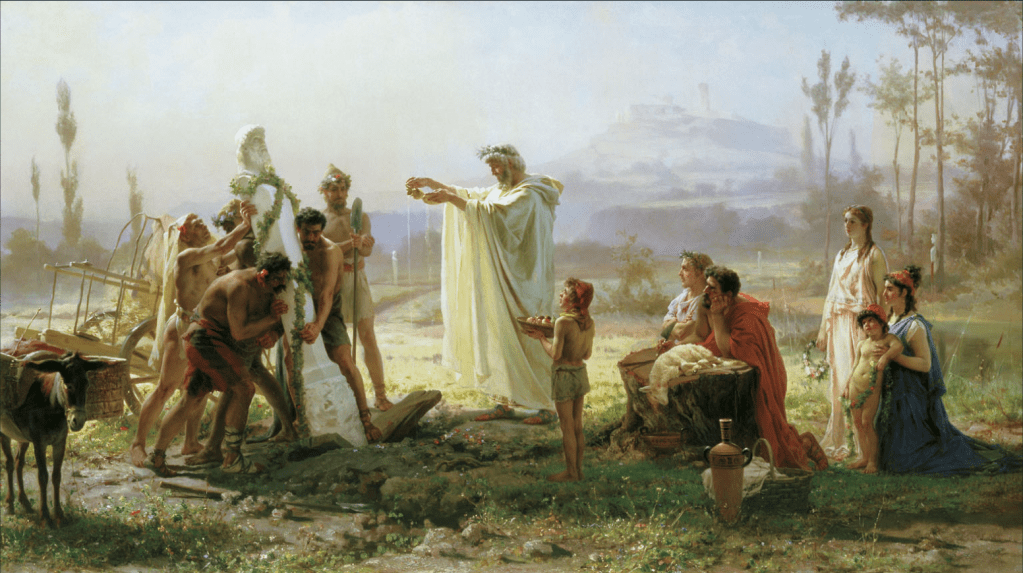

As the months went by, something so instinctual yet still unconscious began to acculturate in my routines for going into nature. In the same way the Ancient Greeks and Romans practiced cults (in its non-pejorative sense) toward their gods, e.g. supplicating Ares before battle, etc. I found myself doing the same for Napoleon and other semi-mythological figures of history.

And even more than this: the most significant dates for me on the calendar began to be the birth and death dates of these individuals, they became the figures of my imagination that I used, as if transactionally, to endure my self-imposed physical challenges– and as time went on their use for me became more broad. I even began to devise increasingly complex codes of morality based on what I took to be the admirable traits of theirs. Still in those days, I wouldn’t have said to anyone that I believed in “God”, or even “gods”, yet in my implicit ways of thinking and acting, I had inadvertently re-developed Paganism as a fifteen year old.

Much of my fascination for the phenomena of religion comes from retrospectively realizing that I wasn’t even trying– religion was the furthest thing from my mind, and yet as though I was ignoring my need for water, I found myself naturally taking a sip from the unconscious fountain of something distinctively religious, acculturating certain habits and routines.

I wouldn’t step foot in a church for the first time in my life until my seventeenth year- and no wonder! With the music of Richard Wagner as my nourishment, I had little knowledge of what I was even lacking.

Nota Bene: looking back, I realize it is only someone who yearns with their entire heart for spiritual nourishment beyond the natural, yet is altogether unable to find it, that can be a devotee of Wagner. Therefore, I think that Tampa– owing to its paradoxical situation of being so religiously diverse, and thusly being without any definite or singular character– is deserving of having the ‘patron saint’ of Wagner.

Let us then consider more deeply the pivotal question: was such a way of seeing reality- contoured by mythological figures, even if for me unconscious- something that I subjectively created and added? A kind of sleight of hand by the imaginative faculties, taking simple qualities found in the natural world and augmenting them into the figures of gods and goddesses? This dynamic forming a feedback loop, one which oscillated between tricking myself into something really being there, and triggering some subsequent emotional response to my thinking something was there (regardless of whether it really was or not)? Or, was this acculturation something that I in fact just found, as though discovering something already there, as said earlier, intelligible as being some innate archetypal organization of human consciousness?

Broadly, it has seemed to me that those who are, whether staunchly or irresolutely, against religion (in its traditional sense) fit into the former camp, whereas those who stand religious commit themselves to some kind of variant of the latter camp– and interestingly enough, the former camp constitutes the view of David Hume, the latter camp those of Immanuel Kant; each constitutive of the massive paradigm shift of modern philosophy.

As the famous story goes, the young Kant was so captivated, so enthralled, yet terrified by Hume’s subjugation of human meaning to the superfluous faculty of imagination, that he awoke from his dogmatic slumber and spent the next twelve years laboring, studying, and incessantly thoroughly considering Hume’s position, and if it could be otherwise.

That it was otherwise, is why we still remember the name Kant– after those twelve years, he vindicated the idea that for human perception and experience to be, in principle, possible whatsoever, it must presuppose certain regulating concepts; concepts such as time and space, cause and effect, etc. Therefore, these concepts were not mere fancies of the imagination, but the necessary conditions to explain how consciousness is possible whatsoever.

Brilliant as Kant was, for our purposes here, we are still more lacking a justification for the reality, the actuality of the sort of cognitive claims made by religions– even with the former camp supplanted by the latter– we are at best left with a partial justification for why we naturally tend to organize reality in a mythological way, yet without any justification for the independent existence of such entities as God, or gods. This is quite fitting, as Kant himself after all endorsed a kind of agnosticism regarding the verifiability of religious claims.

This agnosticism is all too clear when we have such scenes of Kant, who in his heyday stood at the pinnacle of philosophy, when asked why he was a believing Christian, answered with the rather anticlimactic, “Because my Father told me so!”1

Disappointing as such an answer was, perhaps we may empathize with what I believe to be, the greatest under-appreciated story of human history– it is the story of how the heyday of Kant gave way to the heyday of the young German Idealists: Fichte, Schelling, and Hegel. It is a tale of young men who, although baffled by Kant’s logical brilliance, were completely dissatisfied with his treatment of the most important questions of human existence, questions he relegated to the domain of eternal mystery; the onus was now on these youngsters to see if it could be otherwise.

Before jumping headlong into such a mighty tale, a bit more preliminary work is needed. Let us now lay the groundwork for what these young men have to say about both Hume and Kant by discussing what precisely religion is.

What is distinctive of the sort of thing we refer to as religion is, in a sense, ubiquitous. Growing up in (godless) New Tampa, not even I could escape religion2. Even in the secular of seculars, while just trying to go about my daily activities I implicitly adopted habits or norms that resembled bygone religious traditions of the Ancient world.

Yet besides this bare content, one’s daily habits and thoughts don’t need to merely resemble previous religious traditions to be what we refer to as religious– in contrast to this, one’s habitual ways of thinking and being (the kind of thing understood as a “normativity”), despite possibly not resembling traditional religions, are still expressive of the same sort of striving of “religion”.

I can imagine much immediate pushback from such a re-conceiving of religion, yet bear with me fellow friends. I think that if we seriously think through the concept of religion, we find it being expressive of a normative and even cognitive space that is in form equivalent to the spaces connoted as non-religious, i.e. agnostic, atheist, or secular. Even connotatively speaking, the line of demarcation between the two usually would fall on merely a difference in content, i.e. if one has an explicit avowal of the supernatural, the holy, etc.

It is regarding this line of demarcation that I would like to apply some scrutiny. I take it that one’s denial of having ‘traditionally’ religious content, whether that be titled as an apathetic non-religious quietism (agnosticism), or pathos-filled denial of deities (atheism), contrary to the connotative view, does not simply absolve oneself of “religion” in general. All it does rather, is merely place one’s implicit orientation of normativity (ways of thinking and being) around some other governing principle.

Anyone who lives has to constantly make judgments about themselves and the world around them. As Kant himself put it, “Judgment is the minimal unit of [one’s] awareness”. These judgments aren’t simply made on whims, they are deeply embedded in any respective individual’s constellation of commitments. Many of these are implicit or unconscious repetitions- we put the car into reverse when backing out of the driveway, relying on some mechanical understanding that it changes the direction of the wheels. Many other judgments are conscious and novel- it is encountering a homeless person and, depending on what moral commitments one holds oneself to, making judgments to act accordingly.

More holistically, a constellation of commitments is the criterion by which one lives each second of their life. Whether one affords belief in supreme ontological Being, whether one has an overarching ideal they are striving to realize within themselves, whether they live for the notions of happiness, altruism, family or the many other guiding orientations by which we may live life, we base our most significant (and insignificant) judgments off of a constellation of somethings- even if part of that constellation is a privation of something such as atheism3.

We may see that there are as many governing principles as there are answers to the questions: “What do you live for?” or “Why are you doing this?”. In this way, to be involved in the activity of religion (even if not connotatively described as “religious”) is inescapable.4

Yet why am I, in effect, re-conceiving religion to mean more broadly, world-view? My reason for this is profoundly significant to what I will later introduce as, the way the mature German Idealists saw as the only coherent way in which Religion can be conceived: a conception that fully appreciates Religion as the unfolding search for a coherent worldview, specifically as it manifests in particular religions. It begins as a quest that isn’t necessarily aware of its goal from the outset, yet we shall elucidate this idea to its full maturity in the latter articles in this series.

Having mentioned such a view of religion, I would like to give an example: I take it that, though an unprecedented development in the history of religion, the emerging Enlightenment era of secularity rebuking its hitherto content (of a particular deity) is still very much so continuous with what it emerged from, that being Protestantism. And the Enlightenment emerged from Protestantism in an incredibly visceral sense- as simply taking the ‘reformation’ one step further than Luther did- instead of protesting against the authority of the Catholic Church, protesting against the pre-Enlightenment dogmatic conceptions of a supreme Being: God.5 The leaders of the Enlightenment very naturally thought that the uncritical understandings of God were no longer tenable, and so sought to bring about comprehensive changes to society and morality because of this.6

To bring this point to an end: the search for a coherent worldview is doubly the normative and existential search for a criterion by which to live (judgments of our actions depending on our commitments of worldview). If one’s entire life is oriented, explicitly in thought or implicitly in actions, around e.g. family7, happiness, money, we can say that each particular answer is functionally equivalent to what the traditionally religious refer to as “God”8.

We all devote ourselves to or worship something. Even if not explicitly affording a particular belief in a particular god, normatively orienting one’s life around a “God” is inescapable. God, after all, apart from being a linguistically religious term for a particular deity, is also a pragmatic & existential tokening that picks out the most deserving of one’s time and energy, alongside being a logical and conceptual term that picks out that which is Absolute (logically coherent in totality). Hegel makes just this connection when he writes something like “[r]eading the morning newspaper is the ‘realist’s’ morning prayer”.

Now to connect this with the aforementioned youngsters and bring the first part of this article to a close. Hegel, most prominent among them, applies this point just discussed masterfully in his explication of the emerging early Enlightenment war between Faith and Reason9, a titanic upheaval between the old Protestant and Catholic traditions and the nascent Enlightenment way of thinking (deism, agnosticism, and atheism).

In their clash, a distinctively early-Enlightenment conception of Reason (mouthpieced by Hume, Diderot and Voltaire) understands Faith as having a– even if sincerely believed– ultimately contrived or made-up Deity. For this reason, Reason, seeing Faith as a less developed version of itself, is quite confident of convincing Faith of its own inferiority, something it is confident to achieve through disproving or proving highly improbable the cognitive claims of God’s existence.

Reason’s confidence is partially merited as Faith cannot help but see itself, its own rational nature, in Reason’s argumentation. Faith, in the attempt of maintaining itself, either tries to downplay the validity of reasoning (Pascal), or it tries to articulate itself as rationally coherent trying to beat Reason at its own game (Descartes and the ‘rationalist tradition’).

With a view for conceptual clarity, what is Faith, and what is Reason? For Hegel, they constitute a distinction which is only first fully appreciated in the heat of the French Enlightenment. Reason emerges as the concept which Enlightenment-thinkers emphasize as the element of any consciousness which cannot help but be satisfied only through rational justification. In this sense, for the early Enlightenment, Reason is the personification of a new methodology (a form) in securing what we merely take to be “True”, to be actually “True”.

Faith emerges, conversely, as the minimal (& most traditional) form in which a content appears. It is the minimal form precisely because it merely utters its mythology as a given, only attentive to the internal coherence of its mythology, yet not necessarily the meta-coherence of how it coheres with reality more largely. As such a minimal form, it is more prominently characterized by its rich content (especially as accumulated in religion), yet a content with an emerging lack of justification regarding the new & brilliant questions of meta-coherence that are being put to it. How do you justify believing in your mythology over our mythology, e.g. Catholicism over our Protestantism? How do you justify believing in an invisible Being at all?

After meaningfully distinguishing these concepts, Hegel sought to not leave them as a dualism, yet, holistically, to also give credence to their shared unity which they, along with any dualistic opposition, emerge from.

This shared inner-unity is subtle: Faith and the specifically French-Enlightenment conception of Reason are both the Faith and Reason of a person, of a subjectivity, a consciousness. As such, in Hegel’s view, they must be incredibly cautious in how they treat one-another, for being unaware of what the other conceptually is, they run the risk of inadvertently attacking an element of the other which also constitutes themselves. As an example, if Reason denounces Faith for being subjective consciousness’ mere creation, perhaps one to cope with the difficulties of life, is Reason not also denouncing itself, denouncing the part of itself that is just a methodology conceived of and by humans to try and cope better with the difficulties of life, make intelligible the unknown terrors of life? Would it not seem that the distinction between Faith and Reason is rather blurry again, both being just methodologies, forms by which to make reality or life intelligible, bearable, etc.?10

To put it more lucidly, perhaps Reason shouldn’t have an issue with Faith having a content which is its own subjective creation so much as an issue with how minimally (weak & vulnerable to scrutiny) the form Faith exerts itself in choosing a particular content. In this sense, Faith & Reason aren’t so much opposed, as much as they are just two emphases of the same underlying striving.

Yet to advocate for the possibility that they may really be opposed further, if Reason does have an issue with Faith being a merely subjective creation, it must demonstrate how Reason itself is not also a merely subjective creation, (which I take it to be able to do in its successor-developments in German Idealism11), while more difficultly, it must prove that Faith does not also slip in through the door, right on Reason‘s heels, and itself also become more than a mere subjective creation. I take it that such a project to separate Reason & Faith was exhausted by Hume, Kant, and the Neo-Humean who captivated the young German Idealists, Gottlob Schulze.

To summarize: Hegel understands historically that Faith (or traditional religion) is the minimal form through which a fully fleshed out content was able to acculturate, one which in the Enlightenment, confronted with the new questions of its own meta-coherence, seems to struggle in giving a rigorous articulation of itself; conversely, he understands Reason as the newfound appreciation for justifications which give ideas a security that it cannot attain otherwise. Overall, he sees them as two methodologies which cannot be opposed in a monolithic sense, yet rather seem to constantly undermine their own distinction in further comprehending one or the other…

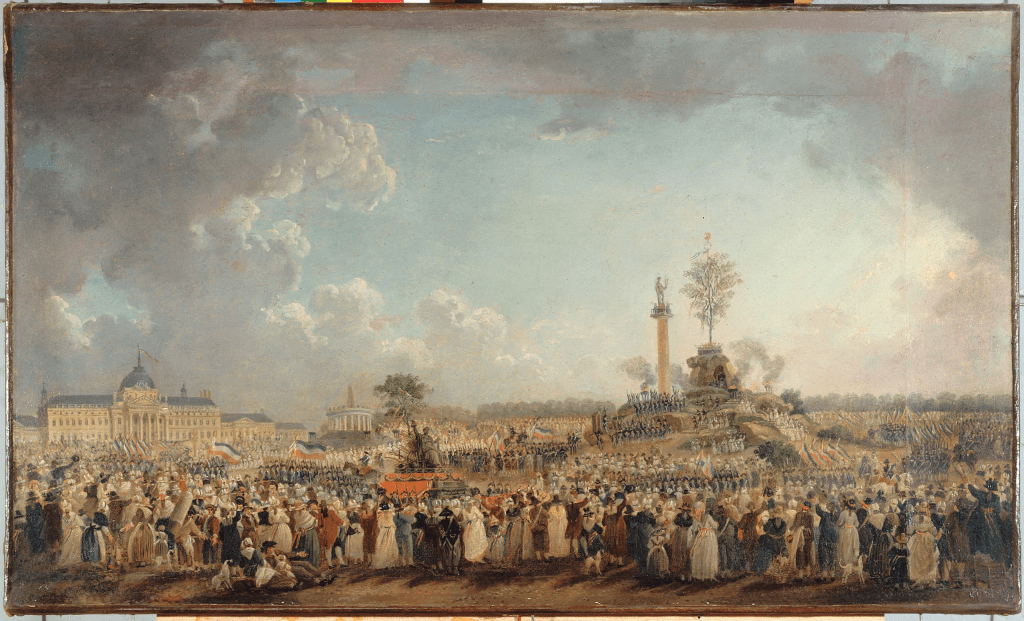

Look no further than the following example of Reason seamlessly flowing into Faith: given that Reason in its early French-Enlightenment iteration has no content besides gloating over its own capacity, this iteration of Reason ironically believes in something even more contentless and immaterial than Faith– the cult of reason!

Perhaps this all sounds absurd, mere circumlocutions which conflate various meanings. Despite the verbosity of the account, it is one that may actually be vindicated in concrete history– specifically the French Revolution, the first time where these debates of theism and atheism were actually mobilized into living breathing life– the French revolutionary government after abolishing Roman Catholicism replaced it with a new official atheist religion titled: The Cult of Reason.

After barely a year, this religion being harshly criticized by the revolutionary Robbespierre, who, following Voltaire’s aphorism that “If there was no God, it would be necessary to invent Him”, realizing Reason to be totally empty of content, thereby won the people over to a successor religion that tried to consciously posit the most rational conception of God: Deism12. Such a project led to the next official religion: The Cult of the Supreme Being.

Suffice to say, this state religion didn’t last too long either, and in Hegel’s account, the debates between faith and reason sadly lapse into a debate over utility– whichever side is more useful should be what one believes in.

Here, one may see a tragic image, one all too familiar today– it is the image that Nietzsche heralded– the individual who, despite their lack of genuine belief in the cognitive claims of religion, still attends and partakes of everything religion has to offer because of the utility it may offer them. Living in such duplicity, such individuals rarely can attain the fruits promised by such religions, and find at most, a diluted cultural or sentimental satisfaction. This way of life is so much more common than we care to acknowledge; if any such individual can count themselves among the readers of this article, know that it is for you I write.13

Conversely, most institutions of religion, either unaware or unconcerned with the contemporary critical environment ushered in by the Enlightenment, neglect to take care to make explicit the significance of their own particular justification (of themselves over every other religion)– justifications, by which I wish to add, that would be able to articulate just how profoundly true they may really be– certainly justifying belief beyond their mere utility.

In recapitulating Hegel’s discussion between Faith and Reason, I have hoped to further justify the ontological inextricability of what we moderns so casually tend to keep and treat as separate: the religious and the secular. In the next part of this article, this groundwork will be essential to how religion shall be maturely conceived in contrast to Kant’s agnosticism and the lapses of our questions into that of utility.

- This nearly comical scene is claimed by Kierkegaard in his diaries, who from his perspective, used this anecdote to draw significance to depending on faith instead of logical argumentation.

↩︎ - As referred to earlier, Tampa has about it this paradoxical character whereby the presence of every single religious demographic, as well as being such a new city, results in the city having an altogether mutually irreligious character especially as compared to most other parts of the U.S.A.

↩︎ - This kind of thinking, that a privation of something is still a something, follows a venerable tradition of ontology inaugurated by Plato’s The Sophist, where Plato argues that non-being or the privation of being is nonetheless still a sub-category of Being.

Alternatively, even disagreeing with the above point, atheism as a cosmological position, with its respective consequences on one’s personal ethical standard, has, at least culturally accultrated into something positive (as opposed to being merely privative). Their hypothetical “creed” has been put quite eloquently by Valentine Tomberg:

“I believe in a single substance, the mother of all forces, which engenders bodies and the consciousness of everything, visible and invisible.

I believe in a single Lord, The Human Mind, the unique son of the substance of the world, born from the substance of the world after centuries of evolution: the encapsulated reflection of the great world, the epiphenomenal light of primordial darkness, the reflection of the real world–evolved through trial and error, not engendered or created, consubstantial with the mother-substance– and through whom the whole world can be reflected.. It is he who–for we human beings, and for our use–has ascended from the shadows of the mother -substance.

He has taken on flesh from matter through the work of evolution, and has become The Human Brain.

Although he is destroyed with each generation that passes he is formed anew in each generation following, according to Heredity. He is summoned to ascend to a comprehensive knowledge of the whole world and to be seated at the right hand of the mother-substance, which will serve him in his mission as judge and legislator, and his reign will never end.

I believe in Evolution, which directs all, which gives life to the inorganic and consciousness to the organic, which proceeds from the mother-substance and fashions the thinking mind. With the mother-substance and the human mind, evolution receives equal authority and importance. It has spoken through universal progress.

I believe in one diligent, universal civilising Science. I acknowledge a single discipline for the elimination of errors and I await the future fruits of collective efforts of the past for the life of the civilization to come. So be it.“

↩︎ - (October 28, 2024) – I have since realized that this position is actually one that has been pioneered in the scholar of Religion, Johnathan Z. Smith. Smith defines Religion quite rightly just as “human activity”. Though, I would say based on my incredibly telegraphic understanding of him, Smith doesn’t fully appreciate just how any human activity is implicitly committing itself to some way of making reality intelligible, i.e. that of a religion.

[Further, as of November 2024, I have learned that this is also precedented by Schelling’s thesis that Christianity, due to its theology, is the only religion which is self-secularizing. …

Further further, as of April 2025, I have learned from a Lord of Spirits episode, that professor Joshua Dowell wrote a book titled Understanding Secular Religions, coming to the almost identical point that I am making here.

Further further further, I have discovered that Charles Taylor has popularized and achived with his book A Secular Age, almost everything I wanted to do with these essays… What beauty to strive and then find what one was trying to do all along…]

↩︎ - In realizing religion to simply be the orienting principle for one’s life and worldview, the end to which our ways of thinking and being are directed, we may entertain equality of religions, what one calls “God”, another calls “Allah”. Indeed, this is the theme of Nathan the Wise, a play by Enlightenment playwright, Gotthold Lessing, with one of his main characters displaying the equivalence (this time, among traditional religions) with the lines— “What makes me to you a Christian, makes you to me a Jew”. Lessing’s characteristically Spinozist conception of religion will be a topic of interest as we proceed.

↩︎ - How fascinating would it have been, if there was an Ecumenical council in which the Enlightenment skeptics and believers could dialogue everything out? Alas, the world-historical process is so much more complex than just ‘talking things out’.

↩︎ - Is it not noble to make one’s orienting principle something like family, such as with the common image of the devoted and selfless mother? I go on to argue that such a mother, and anyone really, can actually do immensely more for their family by explicitly not making their family their entire orienting principle.

↩︎ - I can take this point so much further, and it indeed is a rich point. It is my belief that the particular Ancient Greek ways of life religion/system of ethics– Epicureanism – best describes most self-avowed “non-religious”.

↩︎ - One of the most beautiful strategies Hegel employs in the Phenomenology is personifying concepts. It is a prosopopoeia par excellence. In fact, viewing points of view as incarnate paradigms of thought is one of the many fruits that Hegel’s emphasis on the interconnectedness of reality and its inferential relations brings.

↩︎ - Hegel puts this thusly, “What Enlightenment declares to be an error and a fiction is the very same thing as Enlightenment itself is”. Much of Hegel’s brilliance consists in drawing out distinctions, only to more powerfully undermine them in a way that leaves us with a profounder, more foundational question which we can then focus our attention upon. The order of this series is a good basis for the concept of “Dialectics”.

↩︎ - Specifically, I think Hegel is best able to achieve throughout his work wherever he critiques Kant. Such a critique will be explored later.

↩︎ - Deism is the first religion fully born of man’s conscious reason. Deists believe in the necessity of a creator because they are convinced by the metaphysical arguments that such a “unmoved mover” was necessary to explain why there is something instead of nothing. Fascinatingly, Deists believe in nothing further than that, disregarding the rest of the traditional baggage associated with God, e.g. including if he is a personal being, if he cares about his creation at all, etc. The most notable Deists counted themselves among the American Founding Fathers.

↩︎ - This dilemma is incredibly expressed by Hegel in his Lectures on the Philosophy of Religion: “It is a false idea that these two, faith and free philosophical investigation, can subsist quietly side by side. There is no foundation for maintaining that faith in the content or essential element of positive religion can continue to exist, if reason has convinced itself of the opposite. The Church has, therefore, consistently and justly refused to allow that reason might stand in opposition to faith, and yet be placed under subjection to it. The human spirit in its inmost nature is not something so divided up that two contradictory elements might subsist together in it. If discord has arisen between intellectual insight and religion, and is not overcome in knowledge, it leads to despair, which comes in the place of reconciliation. This despair is reconciliation carried out in a one-sided manner. The one side is cast away, the other alone held fast; but a man cannot win true peace in this way. The one alternative is, for the divided spirit to reject the demands of the intellect and try to return to simple religious feeling. To this, however, the spirit can only attain by doing violence to itself, for the independence of consciousness demands satisfaction, and will not be thrust aside by force; and to renounce independent thought, is not within the power of the healthy mind. Religious feeling becomes yearning hypocrisy, and retains the moment of non-satisfaction. The other alternative is a one-sided attitude of indifference toward religion, which is either left unquestioned and let alone, or is ultimately attacked and opposed. That is the course followed by shallow spirits.”

↩︎

5 Replies to “Apropos of the Grey Clouds (1/3)”