It is far easier to write a Tragedy than a Comedy. With Tragedy being such a formative and relatable element of our human experience, there’s no wonder why it’s so smitten with as a literary and theatrical theme. Yet I wish to ask more deeply, why would anyone pay money to be confronted with a staged resimulation of the worst moments of other people’s lives?

I felt incapacitated by one such literary tragedy in my boyhood. It was the story of a youth who yearned, not for love, for wealth, or for power, but only to know himself. The book follows his exhaustive efforts towards this goal, studying, fasting and the like. At some point, he is convinced by a friend to move out of dark squalor into this friend’s quarters, quarters which this friend rents from a widow and her daughter. The youth moves in, and against his will, begins to agonizingly fall in love with the daughter, and through struggling with and against his feelings of love , despairs over his ability to realize his original goal of purity, resorting to embrace that final despair, that of suicide.1

As with any story we are touched by what we may see ourselves in; and further, we empathize with what may easily become our fate. At that point in my life, I certainly empathized considering myself part of that same quest and it was exactly my participation in that Tragedy, a tragedy that captures the deepest recesses of our hearts, that I would like to speak about.

Do you ever have those days where you just want to write: History is not the soil in which happiness grows, as Hegel pens? That: The periods of happiness in it are the blank pages of history? I can see this all too clearly in my own childhood diaries, where any time of idyll being without entry or mark is overshadowed by a diary brimming with the pen-strokes of ranting and externalizing anger. All I was trying to do was make sense of tragedies, literary or real, participating in our universal activity of confronting an external evil.

What Aristotle realized about the genre of tragedy in his Poetics is that it provides catharsis. People relieve their own individual burdens by empathizing, literally (as the etymology goes) feeling-in the victims. You watch a person just like you go through the whole of a play as they face what you have faced before: terror, delusion, & distress, only now seen under a magnifying glass as a microcosm. It is precisely in feeling-through the actor that you live through a new story, you experience what they experience, thus leaving the theater cleansed, fraught with the weight of human existence.

This is why we partake of art. It is identifying “Me” in a work of art, it is feeling nourished by the very colors and forms, it is grasping, as though it were spread out plainly in the palm of your hand, yourself and the vicissitudes of life.

That much more intimate with those intricate dark crevices of Life, our own silhouette becomes much more visible. What beholding Tragedy gives us is this kind of preparedness against what is guaranteed in Life, that of constantly confronting error, hatred, anxiety, Evil, and the like.

“If you hate a person, you hate something in him that is part of yourself. What isn’t part of ourselves doesn’t disturb us.” – Herman Hesse

“Do you not know that there comes a midnight hour when everyone has to throw off his mask? Do you believe that life will always let itself be mocked? Do you think you can slip away a little before midnight in order to avoid this? […] In every man there is something which to a certain degree prevents him from becoming perfectly transparent to himself; and this may be the case in so high a degree, he may be so inexplicably woven into relationships of life which extend far beyond himself that he almost cannot reveal himself. But he who cannot reveal himself cannot love, and he who cannot love is the most unhappy man of all.“ – S.A. Kierkegaard

Tragedy being so ubiquitous in our lives, it quickly became a popular genre. Looking upon its various colors and shapes, what I appreciate most of all in Tragedy is what it precisely discloses to us about confronting this negative in life as it so inevitably befalls us.

To illustrate this as far as I may, I wish to ask: what is the worst tragedy we may conceive of? I ask not merely in magnitude for something unrealistic like everyone we know instantly dying, but also in quality, i.e. what is most realistic & relatable to our lived human experience.2

I take it that the worst tragedy must be something bad happening to someone who naturally deserves bad least of all: the innocent. Let us take this all the way— how may the worst thing happen to the most innocent person?

This truly innocent person will be resented by people who take themselves to be entirely innocent, and in this, whose grand flaw consists in that they only merely purport to be innocent, or Good. The reason why those who consider themselves Good resent the truly Good person is simple: all jealousy is the negative form of admiration.

Now, this innocent person, being authentically innocent or Good, wants to try to reform the corruption he perceives in those who purport to be Good, yet is suddenly betrayed by a very close friend to those same imitators of the Good. Taking this scenario even further, perhaps these imitators sow outrage among the people against the innocent One, and these crowds, being given the choice between a murderer and the innocent One, decide to exalt this known murderer over the innocent One, showing how lowly they think of the innocent One.

To top this all off, this innocent One is murdered by the most gruesome technology available at the time, his attempt to reform the corrupt mores of those purporting to be Good left utterly crushed. How would you feel? To be beside that innocent One and to feel so despairingly powerless throughout the whole situation?

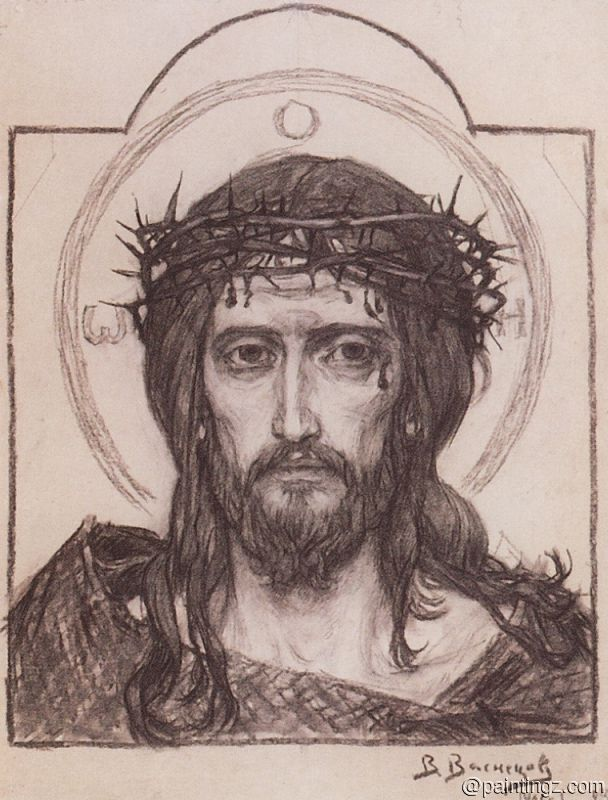

From a purely literary, thematic, or emotional point of view, the story of Jesus Christ is the most augmenting archetype of tragedy known to Man. It is precisely because it is the greatest tragedy (and even more than this as we shall find out later), that it is such a nourishing story. It went completely contrary to every secular cultural notion my upbringing gave me, against thinking of God as the all-powerful, all-sacred infinite and invincible superhero, along with Jesus as a significant ‘hippie’. To finally read the Bible for yourself is a powerful thing.

Imagine my shock to read the account of God as incarnate, i.e. a human being just like me, a man who was not carried around on a throne and just eternally worshiped, but rather, a man who washed the feet of His disciples, saying to them—I have set you an example so that you should do as I have done for you; and even more, that this is what it authentically means to be all-powerful, to be all-sacred.

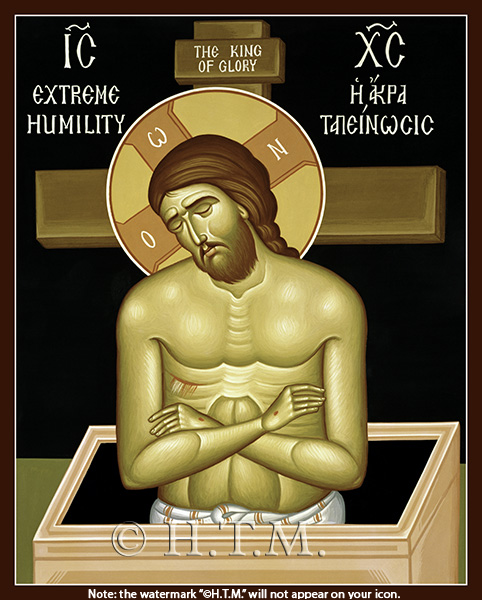

This is the Christian paradox: Christ is King and crucified at the same time. This is the mystery of Pilate’s inscription on the cross of Calvary: Iesus Nazarenus Rex Judaeorum. Almighty and powerless in one. I am reminded of something the aged and defeated Napoleon wrote during the last few years of his life in exile, “Alexander, Caesar, Charlemagne, and myself founded empires. But on what did we rest the creations of our genius? Upon force. Jesus Christ alone founded his empire upon love; and, at this hour, millions of men would die for him.”

The Gospel’s testimony of Christ overturns that deceptively intuitive feeling that authority is equivalent to power. The Pharisees, holding to this dogma, mock Christ on the cross by saying, “If he is the king of Israel, let him come down now from the cross and we will believe in him”. Yet in a kind of psychological projection, they wish only to worship a powerful God who most reminds them of themselves, being above the others and invincible through force. The contradiction latent in that way of thinking, both logically and emotionally, is that true power is not just getting our own way— it rather consists in how we handle things when they do not go our way — in how we confront tragedy. Christ does not need the vulgar earthly conception of power because He has what is even more effective as an authority: Love. A Love which stretches thousands of years further than Caesar or Napoleon’s force ever possibly could.

Instead of having to ponder and study the abstract concept of “Good”, to calculatingly attempt to employ it in our lives, Good itself has incarnated for our sake. No longer is Good the airy fairy idea, yet rather the widely testified living and breathing human being, leaving us hundreds of concrete examples of how to act. Pascal reflecting on this writes, True morality makes fun of ‘morality’.

It is further augmenting, with so many people’s greatest hesitation in faith being the problem of the existence of evil (Theodicy), that so palpably, God in the Christian story did not excuse Himself from such suffering, but rather, personally suffered this excruciating tragedy as a testament of His love for us and in this love, to disclose something to us. To disclose to us, those few among us who may be called “Good” and the majority of us who earn no such title, that even if the worst things happen to us, there is still a final vindication, a final victory of Good, a Resurrection. The worst possible Tragedy, which may become a reality in any of our individual lives at any moment, with this final vindication becomes the best possible Comedy.3 This is the genius latent in Christianity.

What has fascinated me ever since reading the Gospel for the first time as a seventeen-year old was how the entire significance of Christ (the innocent One) takes place against the context of the incumbent ‘officially holy’ Pharisee class (Those who purport to be Good). The Pharisees love Good, indeed, perhaps this is true, yet whatever of their love, they love spuriously so for their love manifests negatively through hating what is not the Good. I am fascinated by this dynamic as I take it that the worst, most subtle Evil consists in being archetypally: An initial Good that clings to Good so fastidiously that it rebukes (abstractly negates) everything not identical to the Good.

This natural deformation of Good is portrayed by none better than the Pharisee, they who identify with Good so much that they gradually become afraid of anything that is not legalistically (according to the letter of the law instead of the spirit) that same Good, resorting to destroy Christ as their source of fear and self-doubt. The radical advancement in the history of religion (history of normativity, ways of thinking & acting) that is introduced by Christ, is in realizing that evil is not the external supervillain, but rather it is me, and that I must accept this part of me, my shadow. The natural pharisaical tendency is to reject our shadow, to repress everything we dislike about ourselves and therefore others (manifesting itself on the organized scale of the Pharisees). Even if I consider myself religious— I am not safe! That even now as I write… I am the Pharisee! What may I do but adopt the attitude of St. Paul’s as he writes, I am the foremost of sinners?4

As I must remind myself each and every day, the point of the story of Christ’s crucifixion is not to scorn the Pharisees and woo an underdog, but rather, it is to plant the convicting spirit that we all would’ve abandoned or murdered Christ if in the same situation. We have all been guilty of, in the same movement of looking up towards the Good, spuriously scorning others with an upturned nose. We shouldn’t be so hasty to change & critique what we see in the world, rather, the worst evil to be on guard against is that which subtly lays dormant within ourselves, ready to spring when we are least prepared to handle it. I used to think so much along the lines of what I can offer the world, what I can do to improve the world, and so seldom is the answer we are taught something like St. Seraphim’s answer— Seek inner peace and thousands around you shall be saved.

When Christ was asked why He was eating with prostitutes and tax-collectors by the Pharisees, who considered them ‘unclean’, He responds thusly: It is not the healthy who need a physician, but the sick; I have not come to call the righteous, but sinners to repentance.

Built into the very bedrock of who Christ is, is this reaction against the natural corrupting force, the pharisaical tendency innate within all of us. Life becomes less so the confrontation of external evil so much as the acceptance and reformation of one’s own internal evil. This is what the greatest tragedy teaches us. It is the greatest tragedy precisely because it is founded on an irony, an irony where the very source of Religion is persecuted by those ‘religious’. Christ protects against an easy proclivity especially for those identifying as Religious, for those who identify as someone who is faithful and therefore just statically Good. Christianity is, in my view, the greatest religion for it best fulfills the goal of religion by being founded on and making explicit so deep the eminent structural irony that many religious of various religions fall into.5

If you are still in want to see this, look only to who our lone innocent man identifies with as he hangs alongside the two thieves after crucified by the ‘religious’— “One of the criminals who were hanged there kept deriding [Christ] and saying, ‘Are you not the Messiah? Save yourself and us!‘ But the other rebuked him, saying, ‘Do you not fear God, since you are under the same sentence of condemnation? And we indeed have been condemned justly, for we are getting what we deserve for our deeds, but this man has done nothing wrong.‘ Then he said, ‘Jesus, remember me when you come in your kingdom.‘ He replied, ‘Truly I tell you, today you will be with me in paradise.'”

Just as the good thief discerns, it is the entire human condition to confront or approach what merely purports to be Good— most of all ourselves. The reason for this proclivity is simple: identifying statically with Good precludes our ability to recognize our own error, or sin. It is not that we do not know that we must treat people well, but that this knowledge, this cognizance of treating people well when we have actual opportunities to do so is constantly obscured throughout the bustle of life. Thus to revitalize against this obscuring, I am grateful for the gift of the Jesus prayer, the gift of going to church and hearing the communion hymn— I will not speak of Thy Mystery to Thine enemies, neither like Judas will I give Thee a kiss; but like the thief will I confess Thee: Remember me, O Lord in Thy Kingdom.

For any of you who champion an ideology, who desire to further an institution, know that it is less so any external enemies or forces that will lead to your undoing— rather, it is the perennial archetype of the internal Pharisaical tendency which presents your greatest foe. If it comes from within, it may only be extinguished within. The story of Christ is founded upon this very irony of all ideology. Only those who are root themselves in this have the conditions to overcome of the ever-haunting irony of institutions betraying their original principles, and succumbing to dogmatism, infinitely-fragmenting partisanship, and eventually, apathy.6

It is at once again utterly ironic and sublime: sublime, that Christ was aware of the precarious attitude of ideological people, even future Christian religious people, to the point of instituting a meta-religious attitude of identifying not as Good, but as a sinner, as someone going to a hospital. Ironic: that this essential teaching of humility has significantly eroded in what I take to be, sorrowfully, the form of Christianity most popularly known to me as a child that off put me for so long, Western Christianity and its decay.

Growing up in this lukewarmness, I have always been inspired by the fervor of Kierkegaard in his claim that to be a Christian is the arduous task of becoming a Christian each and every day. To become a Christian is the fundamental task of Life. It is a similar attitude captured by St. Augustine, “To fall in love with God is the greatest romance; to seek Him is the greatest adventure; to find Him, the greatest human achievement”.

To complete this article, I would like to extend a small line Kierkegaard wrote that inspired this article: Christ is Truth, therefore He was crucified.

Christ is Absolute Love, therefore He was perfectly transparent unto Himself. Christ is utterly vulnerable to Himself, the least insecure Man ever to live. Therefore, for an insecure man, for the man that fears being vulnerable, being honest to himself, for these men to behold Christ, to behold Absolute Good, yields two singular options. They must either kill the idol of themselves (accepting their shadow in vulnerability & repentance), or they must kill Christ.

The Pharisees beheld Christ with insecurity in their hearts, with a fear of being wrong, of losing their official honors & titles, therefore, without killing this idol of themselves in repentance and vulnerable reciprocal-understanding, what I call Communion in another essay, neglecting to understand where those feelings come from within themselves, they repress that which makes them feel those feelings absolutely— Christ.

How transfiguring is it all the more to know that beyond being the greatest literary or thematic tragicomedy, the story of Christ goes beyond mere fiction. Jesus is just as much a documented historical figure with as much evidence as Socrates or Caesar, and thereby to feel that as He hung from the cross, He blessed the very ones who murdered Him— Forgive them Father for they know not what they do.

I have neglected to go beyond the mere literary symbolism of Christianity in this article because what the symbolism itself speaks is enough to bridge the entire literary/reality distinction (it is for another time to approach religion more philosophically). Christ accepts His death, what is His own murder, with extreme humility. He sanctifies what is the whole of life, being crucified & abandoned in some way or another, and thereby discloses the skeleton key of how to confront tragedy or evil: It is, in a habituated total vulnerability to ourselves and others, resisting not evil, yet rather, praying for and even loving our enemies. It is in this way that the Good, no matter what happens to it, shall always prevail.

The entirety of the Gospels, the Bible gives us the confidence to walk through our own crucifixion and to emerge victorious still. The greatest Tragedy turns into the greatest Comedy, Christ rises again. This is why I love the Gospels. It is even yet more miraculous than turning water into wine— it changes sinners into Saints by convicting Saints of their sin. It is the victorious commiseration of God ever alongside us, feeling every feeling we feel. It is the only book I have read and reread yet never fail to find something pragmatic & profound.

Yet more than for these reasons, for the greatest and most honest reason of all, it is the only book that so decisively and absolutely helps me through Life. Thank you Jesus.

“These things I have spoken to you, that in me you may have peace. In the world you shall have distress: but have confidence, I have overcome the world.”

- Natsume Soseki’s Kokoro ↩︎

- Interestingly though, even imaging a tragedy of this kind brings us to think of the Book of Job, which doubtlessly still permeates the cultural psyche. ↩︎

- Remember that Comedy does not strictly mean funny, but more originally and widely, a good ending ↩︎

- There is a fantastic book, How to be a Sinner (Bouteneff), which reconciles the semantics of this penitent attitude, “I am a sinner”, with the potential misuse of it that leads to a distorted emotional relationship with oneself, (something I have heard called “Catholic guilt”). Anyone who is concerned with penitential language may find immense fruit in this work. ↩︎

- As of Autumn 2024 onward, my studies of Schelling have only bolstered this point. Schelling writes in his Freedom Essay that evil is not the negation of Good, but the corruption of Good. What is more powerful than how Christ liberated us from the worst evil, the corruption of the supposedly best religion at the time?

↩︎ - As I connote “infinitely-fragmenting partisanship” as a negative thing, we can draw out the implication. Christianity, since it is the first fully non-dualist religion, has no interest in picking a partisanship, a single side. With non-dualism, we shouldn’t even ever think in terms of two or three sides. Instead, we are called to mediate between sides through dialogue & humility.

My first exposure to this radical way of thinking was when I asked an abbot of a monastery once about if I should be generally weary of philosophy, or if I should keep trying to find fruit in it. He did not tell me to pick one of the two sides I presented, but simply gave me an answer which implicitly mediated between them, “try to talk to the people in your community about what you read.” ↩︎

2 Replies to “The Crown of All Literary Criticism”